Listen to the introduction

With General Secretary Xi Jinping having consolidated his third term at the 20th National Party Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the installation of loyalists to the Politburo Standing Committee, there is greater clarity as to the ideological nature of Xi’s leadership for the foreseeable future. In the build-up to the 20th Party Congress, a series of essays emerged focusing on Xi Jinping cementing a third term as General Secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) and his future plans for China.

These essays dwelled on the question of whether China has peaked or will it continue to rise? These lines of enquiry were raised in relation to what each scenario would mean for relations with China and the world?

The questions in themselves represent opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of thinking about the direction of China, where it is going and what it means for U.S.-China strategic competition and global order. Notwithstanding their importance and analytical rigor, what about the consequences of China failing and what it means for the world?

China failing could entail many scenarios including its socio-economic development significantly slowed, fragmented, or regressing because of a financial collapse, bursting of the property bubble or some other disruption such as the COVID-19 induced economic slowdown. The consequences of these scenarios would not be limited to China.

The Middle Kingdom is the home to the lion share of the world’s global production network, the biggest trading partner for all its neighbors, and as seen during the COVID-19 pandemic, a disruption of supply chains within China reverberates globally causing inflation, shortages of goods, and economic turmoil.

On the one hand, Hal Brands in his April 2022 Foreign Policy essay ‘The Dangers of China’s Decline’ highlighted the dangers associated with a slowing Chinese economy. His argument is centered on China’s socio-economic development miracle fading and its leaders becoming more inclined to take risks.

Brands stresses that Chinese leaders aim to lock in as many strategic gains as possible in the next 10 years. Their hope, according to Brands, is that they improve the favorability of China’s external environment and its place in the international economy as the world becomes more constrained by domestic economic, political, and social contradictions.

Oriana Skylar Mastro and Derek Scissors, in contrast, in their August 2022 Foreign Affairs essay ‘China Hasn’t Reached the Peak of Its Power: Why Beijing Can Afford to Bide Its Time’ argue that China hasn’t reached the peak of its power and as a result China can afford to bide its time when it comes to Taiwan. They offer words of caution for those that see China’s demise through the inevitability of its impending demographic crunch.

This paper aims to migrate away from the question of whether China has peaked or will it continue to rise to a focus on the consequences of China failing and what that means for the world.

To achieve this objective, this paper uses the lens of soft power paucity, impotent partnerships and economic fragility to argue that the slowing, fragmentation, or regression of China’s socio-economic development would have negative consequences for global economic stability and growth due to its central position in the global production network.

Based on this argument, the author wishes to resituate the discussion about “peak China” to one that attempts to understand the global implications of a stagnant China.

Soft Power Paucity and Selective Diversification

Brands, Mastro and Scissors provide deep insight into potential trajectories of China and in many ways, they are both on target with their assessments. Brands is correct in arguing that China has peaked in terms of power at the absolute level.

The unenviable demographic burden is placing an increasingly heavy economic burden on the socio-economic prosperity and sustainability of China’s growth model. Not only does the socio-economic outlook for China look bleak, so does its geopolitical position with deepening unfavorable ratings over a period of time.

To illustrate, recent polling by PEW, GENRON, ISEAS and a jointly commissioned survey by the Korea JoongAng Daily and the Seoul-based East Asia Institute (EAI) and conducted by Hankook Research on perceptions of China, all depict China as unreliable, low in trust or unfavorable.

The recent PEW poll focuses on China’s unfavorability from the point of view of human rights, a result that will likely be magnified after the release of the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner (OHCHR) assessment of human rights concerns in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region People’s Republic of China at the end of August 2022.

The ISEAS 2022 Survey Report in contrast reflects the bipolar anxieties and pragmatism Southeast Asian countries have about the economic opportunities associated with China’s return to economic centrality in the region but also what Chinese regional hegemony will mean for their strategic autonomy.

The survey found that 58.1 percent of Southeast Asian states expressed distrust towards China and that “49.6 percent fear that China could use economic and military power to threaten their country’s interest and sovereignty.”

Similarly, the GENRON poll highlights that while pessimism about China is pervasive in Japan, Japanese citizens understand the importance of the economic relationship with China.

These surveys show that the current trajectory of Chinese foreign policy is having the opposite effect of Xi Jinping’s intention “to introduce Chinese culture abroad and strive to shape a reliable, admirable and respectable image of China.”

In fact, countries such as Japan are engaged in a selective diversification process from China in which they build resilience into their supply chains and manufacturing footprint in the region by working with like-minded countries to build alternative supply chains in Southeast Asia and South Asia.

Concomitantly, the China-based Japanese manufacturing model has been revamped to build in China, by Chinese, for Chinese with Japanese technologies. This strategy is meant to create disincentives to engage in the kind of vandalism and economic coercion the Japanese experienced in 2010 and 2021 after the arrest of a Chinese fisherman and the nationalization of the Senkaku islands, respectively.

Japan is not alone in this selective diversification process. Taiwan has engaged in the New Southbound Policy pivoting its manufacturing to Southeast Asia and India.18 The U.S. under both the Trump and Biden administrations has encouraged reshoring and friendshoring of manufacturing as part of their Make America Great Again (MAGA) and Build Back Better (BBB) programs.

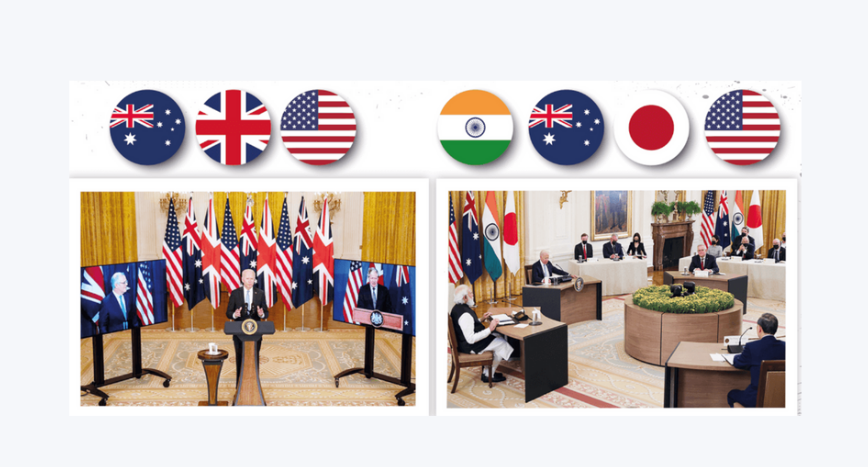

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) has also been leveraged to address “regional infrastructure needs and coordinate respective approaches to deliver transparent, high-standards infrastructure” in an effort to create alternatives to a global production network and its associated supply chain being overly concentrated in any one country.

This selective diversification away from China towards Southeast Asia and South Asia has limits because of human capital, experience and size limitations. Notwithstanding the limits of selective diversification away from China, the trend means China will be less connected to the global economy and not accruing the economic benefits associated with being the center of the global production network.

China’s paucity in soft power with the markets it depends on for sustained economic growth hand-in-hand with the selective diversification seen in relation to China’s behavior and treatment of counterparts will place further downward pressure on its decelerating economy.

Slower growth translates into fewer jobs, lower consumption and as Daniel H. Rosen, founding partner of Rhodium Group argues, “the CCP will have less room to maneuver at home. With less spending power, Chinese leaders will have to worry more about social stability.”

Impotent Partnerships

In its backyard, China has no alliances save for North Korea. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) by contrast continues to expand with Belarus’ accession to the organization.

Moreover, Iran is said to be signing a commitment memorandum for the sake of becoming a SCO member-state, and preparations are being formalized regarding the status of Egypt, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia as dialogue partners in addition to granting dialogue partnership to Bahrain and the Maldives.

Despite this expansion according to Yamei Xue and Benjamin M. Makengo, the SCO “faces challenges and development difficulties on its way forward.

These include the facts of: the intensification of great power game in the region, the weakness of the sense of community between its member-states and the transformation of cooperation patterns after the expansion. Looking ahead, the Shanghai Spirit will guide its multilateral cooperation vision.”

It should also be noted that the SCO’s inclusion of rivals India and Pakistan means the values enshrined in the “Shanghai Spirit” of “mutual trust, equality, respect for cultural diversity, and common prosperity” among members and “non-alignment, non-targeting any third party and inclusiveness” in relation to non-members are limited by their lowest common denominator of its members.

In short, India participates in the SCO to check Pakistan’s influence and to ensure that the organization does not evolve in a trajectory that would be detrimental to its interests.

It is difficult to visualize this partnership evolving to function like the Quad, NATO or the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) with its current membership.

In the case of Sino-Russo relations, they are not as aligned as the February 4, 2022 Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on ‘International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development’ might lead us to conclude after the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The invasion has placed Xi Jinping’s China in the position of contradicting its own Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence by not overtly criticizing the invasion of Ukraine.

Furthermore, as Evan A. Feigenbaum of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace writes, it has compelled China to do the “Beijing straddle.”

On the one hand, “China will provide diplomatic support for Russia and broad commitments to a Beijing-Moscow entente whose principal rationale and focus is to counterbalance Washington and backfoot the favored global institutions and policy preferences of the transatlantic West and Japan.

On the other hand, China will continue de facto compliance with Western sanctions to avoid painting a target on its own back, and it will deploy mealy-mouthed language about “peace” and “stability” aimed at placating the Central Asian nations and partners in the Global South that are uneasy about Moscow’s war in Ukraine.”

While not internationally isolated, China’s motley crew of partners within the SCO, its “radioactive partner” Russia, and its courtship of the Global South suggest that the economic lifelines China will need to maintain socio-economic stability in the years to come will be less dependable than China would like.

The SCO members remain heterogeneous in their levels of development, quality of governance and cohesiveness. Expecting strong economic synergy and dynamism from the SCO is unrealistic and will not be sufficient to deal with the structural and geopolitical downward pressures being faced by China.

Putin’s Russia will remain isolated for the foreseeable future. Deepening economic engagement with Russia by China could potentially lead to secondary sanctions on China, which Beijing does not welcome.

Notwithstanding Russian and Chinese alignment in their efforts to weaken Western-led international institutions and norms, China understands that economic interdependence with rich developed states is irreplaceable both in terms of Chinese exports but also technological infusion.

Lastly, nations of the Global South has been badly affected by COVID-19 and the invasion of Ukraine by Russia. They are facing food security issues, high inflation, unsustainable debt, growing instability from non- traditional security challenges, climate change, and the lingering effects of COVID-19.

They are not in a position to be strong economic partners for China and to help mitigate the growing number of domestic contradictions in the Chinese economy.

Economic Fragility

At the economic level, the central government is putting more and more emphasis on state-owned enterprises (SOEs). Nicolas Borst argues that the strengthening of SOEs is “a tool for the implementation of government policy.” Borst posits that “Xi’s embrace of SOEs stems from a belief that they can advance his goals of strengthening the Chinese Communist Party and reclaiming China’s former national greatness.”

The data suggests different. According to Diego A. Cerdeiro and Cian Ruane, “SOEs have lower revenue productivity (revenue over inputs) and capital productivity (revenue over capital) than private firms.” In short, they are a drag on the economy while offering some stability for workers.

The expanding presence of less productive and less competitive SOEs in the Chinese economy will further challenge maintaining business dynamism. However, it does not mean that the private sector is in complete retreat or being suppressed by the central government, according to The Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE). In fact, PIIE found that the private sector is expanding rapidly and at a faster rate than SOEs.

This view is rebutted by Raj Verma, who argues that “the declining role of private enterprises and the increasing role of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) in the economy, and the extension of Communist Party influence in both SOEs and the private sector through the Party’s Organization Department and United Front Work Department.”

Verma stresses “that the increasing role of the state in the economy over the past decade has stifled growth through a decline in ‘total factor productivity’ because of increasing misallocation of resources.

Centralisation, with associated losses in efficiency, objectivity, agility, speed and finesse regarding allocations of risks and investment, has debilitated decentralised decision-making and reduced the incentives for undertaking risks and innovation.”

When considering domestic consumption, Gatley found that since 2020, household consumption has remained weak, persistently staying below the 2017-19 trend.

CEIC Research group echoed this weak domestic consumption growth which was at 38.696 percent in 2016 and 38.484 percent in 2021, a drop that encompasses the pre-COVID-19 period.

This downward trend does not include the decline in domestic consumption associated with the 2022 widespread lockdowns in Mainland China associated with the Dynamic Zero COVID-19 policy.

What Happens to China Doesn’t Stay in China

With these sober economic realities in mind, at the macro level or the absolute level, China will be trapped by its own domestic contradictions. Here Brands overlooks the relative ability of the Chinese state to direct in a very narrow sphere, power and enormous amounts of power.

Mastro and Scissors are correct in saying that even as China’s power continues to decline over a period of time, its ability to concentrate an enormous amount of power on a particular problem, in this case, reunification with Taiwan will only increase.

These three authors provide sensible analysis as to the strategic challenge of what a peaked China or still growing China means for U.S.-China strategic competition. Nonetheless, both approaches are myopic regarding the future if China does fail.

Key questions we need to ask are what does it mean for the global economy? What does it mean for socio-economic and political stability at home? How will this spill over within the region? Do we have interest in ensuring that the Chinese economy and society remains stable, sustainable, and engaged in the global economy? I would argue yes.

With all of China’s neighbors biggest trading partner being China, with over $560 billion of bilateral trade between the United States and China, with China still being the center of global production for many of the goods that we consume every day, a failed China or China that collapses economically will have dire consequences for the global economy, for inflation, and for the production of everyday goods that we take for granted, not to mention the potential for enormous civil conflict as a social welfare system and political control start to break down.

If this is indeed the case, does the United States and like-minded countries have an interest in supporting and helping China evolve in a way that is more sustainable, more open, more proactive?

The answer is clearly yes. The consequences of a failed China and domestic instability in China will not just remain in China.

It is useful to look at how conflict domestically can affect international society. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is an illustrative example.

The conflict has caused food security issues throughout the Global South, devastated the Ukrainian economy to the tune of at least a 45 percent decrease in GDP according to the World Bank, and what we’ve seen in terms of supply chains breaking down in that part of the world will have an impact on supply chains and the economy globally.

An equivalent breakdown of the Chinese economy would affect Southeast Asia, Japan, and Korea, as well as Taiwan and other economies. It’s not only their manufacturing footprint, which would be impacted, but their biggest provider of goods that has allowed them to develop and increase the quality of life over the past 40 years.

This, in tandem with Chinese debt could create a global economic disruption that would have long lasting and impactful consequences on the whole region as Brad Setser has argued.

In reality, it is difficult to predict the depth and nature of the impact of a slowing, fragmentation, or regression of the Chinese economy. What is clear is that the tumbling of the Chinese economic house of cards, in whatever form that manifests, would have profoundly negative global socio-economic consequences. It would make the supply chain disruptions and inflation associated with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine look miniscule.

Deterring a forced reunification with Taiwan, China’s determined effort to revise the regional security order in the Indo-Pacific and its efforts to dilute the rules-based international order will continue to be critical strategic challenges to manage in the years to come.

Nonetheless, we need to also find avenues to engage with China in such a way that its socio-economic stability remains intact. This challenge will require a partner in Beijing, one that would be willing to work within the existing rules-based order rather than challenge it.

Download the full paper:

This paper was first published in November 2022 at https://www.isdp.eu/publication/the-dangers-of-a-stagnant-china-the-necessity-of-awkward-coexistence/.

Leave a comment