Listen to the paper

The Lowy Institute’s Asia Power Index empirically demonstrates that India, South Korea, and Japan belong to the same grouping of states in terms of their comprehensive national power – the middle powers. Book ending this group of states includes a heterogeneous set of countries with the U.S. and China at the apex of the list and small countries or powers such as Nepal, North Korea, and the Maldives at the bottom end of the power ranking. This middle power grouping tell us little about the nature of their diplomacy as the group is politically and economically heterogenous and comprises of countries as diverse as Japan, South Korea, Iran, Vietnam, Indonesia, and India.

Nonetheless, there are countries such as India, South Korea, and Japan that converge in their interests in promoting a rules-based order, in balancing the growing weight of China in the Indo-Pacific region, and in cooperating on emerging issues. These issues include resilience initiatives, technology, the provision, and protection of global public goods such as health infrastructure, preserving the status quo across the Taiwan Strait, and infrastructure and connectivity.

Notions of middle powers, meanwhile, continue to evolve. Scholars such as Chapnick (2011), Cooper (2016) and Higgot (1990) discussed middle powers in terms of functional, normative, and hierarchical behavior, niche diplomacy and coalition building. Ping in contrast puts forward the concept of hybridization, that states that are empirically defined and that middle powers have an “innate statecraft and perceived power” as a result of their size.

On the flipside, Robertson rejects the notion of middle power using examples such as MIKTA arguing that the middle power concept is definitionally powerless. Still others such as Nagy (2021) argue that effective middle powers engage in neo-middle power diplomacy characterized by lobbying, insulating, and rulemaking in the realms of security, trade, and international law, to protect their national interests from Sino-U.S. strategic competition.

In short, reflecting the new realities of U.S.-China strategic competition and a U.S. partner that is less reliable on the international stage, neo-middle power diplomacy requires pragmatic, realistic and regionally focused diplomacy in lieu of normative agendas which can include but are not exclusive to the promotion of human rights, human security and feminist foreign policy initiatives that while important make it more difficult to achieve tangible results that meet national interests.

Through the above lens, the trifecta of India, South Korea, and Japan represent a middle power constellation that can provide global public goods to the Indo-Pacific that are tangentially linked to each country’s national interests. By aligning their comparative advantages, Japan, South Korea, and India can engage in synergistic middle power diplomacy that aligns interests and capabilities towards deliverable and sustainable foreign policy coordination.

Taking up Resilience

Resilience has migrated to the center of economic security policy planning since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. Disruptions associated with the lockdowns in the China-based global production networks strained a variety of supply chains bringing acute clarity to many states that they needed to build broader and deeper resilience into supply chains to ensure that a breakdown or disruption in one part of the global supply chain would not disrupt economic security.

In addition to the disruptions brought about by COVID-19 related supply chain disruptions, states including Japan, India, and South Korea have become acutely aware of the potential for supply chain weaponization and that economic coercion can be an additional source of disruption. This has resulted in enhanced unililateral, minilateral, and multilateral cooperation that focuses on resilience and economic security through derisking or selective diversification.

Japan, India, and Australia have already invested in the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI). The recent G7 Hiroshima Summit held a session that was entirely focused on “Economic Resilience and Economic Security” and the G7 Leaders’ related a Statement on Economic Resilience and Economic Security. Broader coordination between South Korea, Japan, and India in contributing to supply chain resilience, de-risking and joint economic security at a trilateral level but also plugging into existing initiatives such as the SCRI represents an opportunity to match comparative advantages to economic security needs.

New Delhi, Seoul, and Tokyo should approach their cooperation in a manner that is pragmatic, realistic, and regionally focused rather than diluting resources through the expansive Indo-Pacific region. By way of example, the trifecta could focus on South Asia or Southeast Asia resilience by enhancing de-risking initiatives and SCRI through policy coordination including but not exclusive to financing, labor coordination, and human capital development that inculcates more resilience into regional supply chains and economy.

The Pacific Island is another subregion within the Indo-Pacific that may be ripe for trilateral middle power coordination to deliver environmental resilient initiatives to a part of the world facing existential environmental threats. A “plug-in” approach to resilience initiatives allows for trilateral cooperation within pre-existing frameworks without the need to formulate new cooperation platforms. To illustrate, South Korea could potential plug into the SCRI of Australia, Japan, and India.

Focus on Technology

Technology cooperation is another area where India-Japan-South Korea middle power synergy in the Indo-Pacific have a role to play. All three states recognize the importance of technologies such as AI, quantum computing, and the digital economy.

There is consensus that AI and quantum computing will shape the region’s economy, societies, and the relationship between governments and their citizens. Coordinating policies in the area of AI, quantum computing, and the digital economy will be important in ensuring that transparent rules govern these technologies and their development, so they are consistent with democratic institutions and the rule of law.

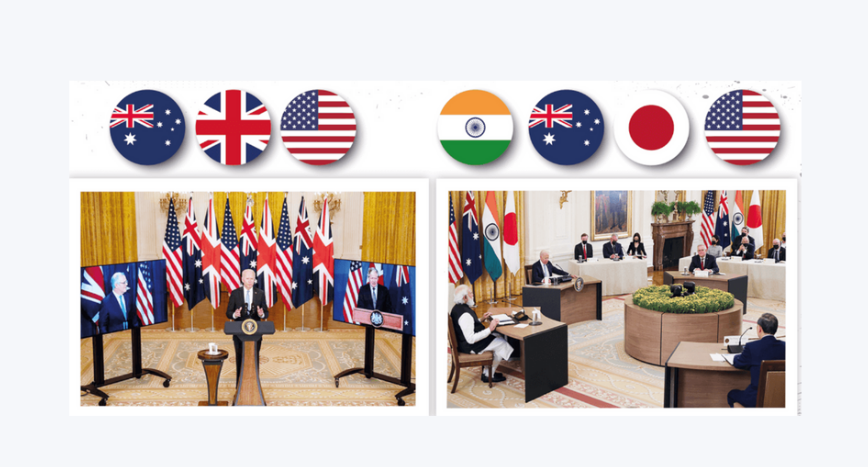

Trilateral cooperation can take place by plugging into existing minilaterals such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) and or the AI and quantum computing components of AUKUS. They can also be standalone forms of cooperation for New Delhi, Seoul, and Tokyo.

In the case of the Quad and AUKUS, both minilaterals have technological pillars. Creating interfaces for engaging as a trilateral partnership that would add expertise, capital, and a critical mass of resources will have a high likelihood of success if New Delhi, Seoul, and Tokyo could package their trilateral cooperation into deliverables.

For example, pooling research and development resources, harmonizing regulatory and legal frameworks, the middle power trifecta can add value to these pre-existing minilaterals through initiatives that are already working synergistically in the areas of AI and quantum computing. In the case of the latter, standalone technological cooperation between India, South Korea, and Japan can occur.

At the high level, semi-conductor manufacturing and human capital should be invested in to contribute to building an alternative semi-conductor production center that is less vulnerable to economic coercion or supply chain weaponization.

Coordination on export controls, AI and quantum computing research and development can not only contribute to advancing technological development but also building more resilience into technology supply chains.

Proactively supporting initiatives such as the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) that includes proposals for technological cooperation is another minilateral/multilateral organization where the collective weight of India, Japan and South Korea could shape how technology develops in the region.

Provision of Public Goods

The broader Indo-Pacific region continues to have a paucity in infrastructure and connectivity, thereby hampering development. Enhancing coordination of financing for infrastructure and connectivity, pooling resources, and joint planning of projects can lead India, Japan, and South Korea to contribute to development and building more strategic autonomy into the region. Increased development and interconnectivity foster deeper economic integration. This has the potential to deepen strategic autonomy of subregions such as Southeast Asia so that they make decisions that are based more on their national interests and less on their asymmetric economic relationship with China.

Plugging into the SCRI, the Australia, U.S., and Japan trilateral partnership for infrastructure investment in the Indo-Pacific or including South Korea in the Blue Dot Network are all avenues to inculcate this middle power trifecta into existing infrastructure and connectivity initiatives. There is also space for New Delhi, Seoul, and Tokyo to focus their public good provision at the subregional level in the areas of health or digital infrastructure, environmental initiatives that help stem the negative effects of rising sea levels, as well as water, food and energy security.

Towards Peace and Stability

Coordinated middle power diplomacy between New Delhi, Seoul, and Tokyo should also be leveraged to preserve the existing rules-based order in the Indo-Pacific. Initiatives could include joint diplomatic statements on the importance of peace and stability across the Taiwan Strait within the context of the so-called “One China” policy, the legitimacy of the 2016 Permanent Court of Arbitration decision against China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea or enhancing sanctions enforcement on North Korea.

Supporting the G7 Leaders’ Statement on Economic Resilience and Economic Security, the Declaration Against Arbitrary Detention in Stateto State Relations or calls for the comprehensive, irreversible, verifiable denuclearization of North Korea’s WMD program are other areas that Seoul, Tokyo, and New Delhi could throw their collective weight behind to promote peace and stability in the Indo-Pacific region.

Without a doubt this will not take place without a quid-pro-quo among New Delhi, Seoul, and Tokyo in the case of denuclearization of North Korea’s WMD. India would likely want more coordinated diplomatic pressure on Pakistan to compel them to denuclearize or more forceful statements related to China’s recent actions in the Tawang sector of Arunachal Pradesh state or in the Galwan Valley.

Conclusion

The dynamic changes and challenges that face the Indo-Pacific region are taking place in the context of the intensification of U.S.-China strategic competition. To avoid being shaped by the strategic competition, middle powers such as South Korea, India, and Japan need to cooperate proactively and pragmatically to secure their national interests.

To accomplish these objectives, a variety of formulas exists in which the middle power trifecta uses their collective comparative advantages to develop new sustainable and meaningful initiatives. These could be stand-alone trilateral cooperation or through plugging into pre-existing minilalteral or multilateral initiatives like the Quad, AUKUS, and IPEF.

Both routes should be pursued to align interests and capabilities towards deliverable foreign policy coordination that is pragmatic, realistic, and regionally focused. New Delhi, Seoul, and Tokyo should ensure that they coordinate their diplomacy by lobbying, insulating, and rulemaking in the realms of security, trade, and international law, to protect their national interests from Sino-U.S. strategic competition.

Source: https://www.isdp.eu/publication/pivotal-states-global-south-and-india-south-korea-relations/.

Download the paper:

Leave a comment