Listen to the introduction

Middle powers in the Indo-Pacific are faced with a trifecta of pressures including China’s re-emergence as central pole in the region, deepening Sino-U.S. strategic competition, and questions related to U.S. leadership in the region. Specific concerns related to China include maritime security, the openness of the emerging digital economy, and the practice of coercive economic behavior, to which middle powers are vulnerable.

To respond to these pressures, some middle powers are adapting to these changing dynamics and transforming their middle power diplomacy towards what the author coins as neo-middle power diplomacy.

This new type of diplomacy proactively engages in behavior which includes lobbying, insulating, and rulemaking in the realms of security, trade and international law, and aims to ensure that middle powers’ interests are not affected by the Sino-US strategic competition.

In the 1990s, scholars such as Soeya (2005) argued that “[m]iddle [p]ower does not just mean a state’s size or military or economic power. Rather, ‘middle power diplomacy’ is defined by the issue area where a state invests its resources and knowledge.”

This functional approach contrasted the normative character of middle powers such as Australia, Canada and arguably Japan in buttressing international institutions that focused on human rights, environmental issues and even arms regulations (Behringer, 2005). These roles were facilitated by a predictable, United States-led international rules-based order.

Fast forward to the 2010s, the international system looks very different. The change in the balance of power related to China’s rise is, for middle powers, aggravated by their deepening concerns about the United States’ (US) leadership in the region.

Perceived as real unilateralism by the US under the most recent banner of America First makes continuance of their post-1940s sustained stabilizing presence in the region questionable (White, 2013).

Furthermore, China is now recognized as a strategic rival by the US itself (DoD, 2019). China is thus successfully challenging the US’ decades long security architecture in what is now known as the Indo-Pacific (Goh, 2019).

Specific challenges include maritime security, openness of the emerging digital economy, and a practiced China-state behavior of economic coercion (Nagy, 2020).

Middle powers allied or partnered with the US are thus vulnerable in all three areas as their relationship with the US is ripe to be exploited by China. In fact, increasingly powerful and revisionist China is actively attempting to weaken their support for US foreign policies by targeting them.

Recent examples include economic coercion against South Korea after the US sponsored THAAD missile system was installed in the fall of 2017 (Yang, 2019). China also employed similar punitive economic tactics against Canada in 2018, but additionally added the illegal practice of hostage diplomacy, by arbitrarily detaining Canadians Michael Kovrig and Michael Spavor after the legal arrest for extradition to the US of Huawei executive Meng Wangzhou (Inkster, 2019).

Thus, China’s threats and aggressive imperial policies signal a new form of middle power diplomacy may be required. Indeed, when combined with the increasing fluidity of middle powers relative to each other and compared to the great power capacity and the behavior of the US and China, a new middle power diplomacy is desperately needed!

What arguably needs to emerge during the 2020s, as the damaging consequences of US-China strategic rivalry mount principally in the Indo-Pacific, is a form of middle powers diplomacy which retains relevance and provides greater agency.

Indeed, middle powers are already aligning to adapt to these changing dynamics. With that in mind, the conundrum that this paper aims to explore includes: why middle powers are transforming their middle power diplomacy and what are concrete manifestations of that transformation.

Read more: Japan-Australia Cooperation: Middle Powers Rising in the Indo-Pacific

Key lines of inquiry to delve into this puzzle include: 1) How do middle powers understand the relationship between great power rivalry and its impact on the development of the Indo-Pacific?; 2) In what ways are they transforming their middle power diplomacy; and 3) Is their formal or informal institutionalization of middle power diplomacy?

To achieve this objective, this paper explores how traditional definitions of middle power diplomacy that focus on a normative, functional and hierarchical approach are transforming.

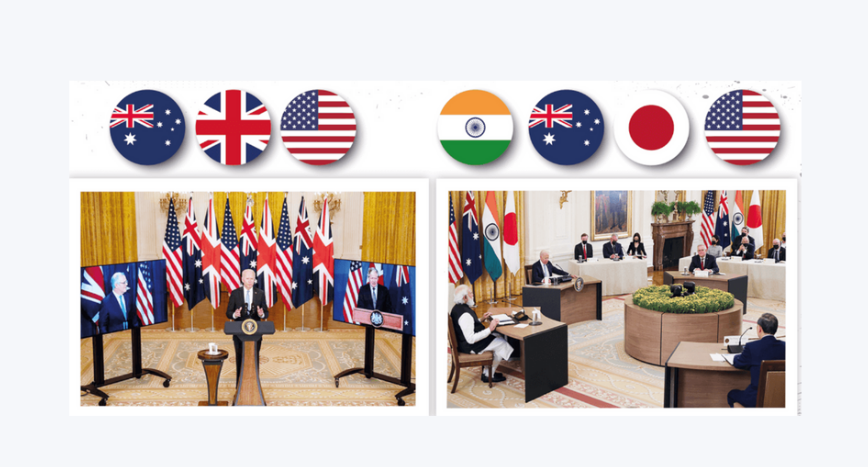

A more proactive diplomacy, or what I term – neo-middle power diplomacy – that engages in behavior that could be categorized as lobbying, insulating, and rule-making in the realms of security, trade and international law is emerging.

While still normative in nature and committed to buttressing international law, what distinguishes neo-middle power diplomacy from the traditional form is that middle powers align to ensure that their national interests are not deleteriously affected by the deepening strategic competition between the great powers US and China.

Middle powers actively balance against both China and the US and their diplomacy migrates beyond advocating for human rights, human security and other so-called “soft” international issues to a diplomacy that cultivates a critical mass of capabilities in order to constrain, lobby, and advocate for their collective middle powers national interests.

This is a systemic shift which changes the behavior of, in particular US allied or partnered middle powers, who will at times align with the US, but germanely at times in not.

This paper has four sections. The first section serves to introduce the concerns of middle powers in the Indo-Pacific. The second section then briefly discusses middle power diplomacy theory to build upon middle power theory. The central purpose of this section is to articulate for what the I call neo-middle power diplomacy.

The third section will then look at examples in which neo-middle power diplomacy is being practiced: 1) maritime security; 2) the digital economy; and 3) economic cooperation. These three cases are not meant to be an exhaustive list of neo-middle power diplomacy but contemporaneous examples that indeed demonstrate that middle powers are transforming their diplomacy to meet the challenges and opportunities in the Indo-Pacific that is becoming increasingly framed by the strategic competition between the US and China. The fourth section will close this paper and propose four areas that middle powers should focus on to create a sustainable and consequential middle power alignment.

Dowload the paper:

Leave a comment