The Global South, a term used to describe countries that are less developed or emerging economies compared to the Global North (Western countries led by the U.S.), is often seen as a unified entity in international relations. It denotes unity of purpose, a shared worldview, and an alternative to the present rules-based order sometimes called a Liberal International Order (LIO). The problem with this formulation is that this monolithic representation is inherently flawed due to its oversimplification of the complexities and heterogeneity within these countries.

This chapter will critically examine the concept of the Global South and explore why its current structure and characteristics limit its ability to support a LIO. It will use Global South interchangeably with developing countries, a term that the author feels is less political and more accurate when speaking of the heterogeneous group of countries that falls under the contentious term Global South.

Moreover, this chapter argues that the developed countries of the so-called West should self-strengthen their own economic, political, diplomatic, and security pillars to outcompete authoritarian states such as China, Russia, and Iran and non-state actors that are interested in revising the current rule-based order, seemingly in consideration of the needs of the developing world.

Flawed Concept of the Global South

The Global South as a concept tends to homogenize a vast and diverse range of countries, with differing political, economic, and social realities. To illustrate, India, China, Nepal, Kenya, Brazil, Kenya, and the Pacific Islands are just some of the countries that make up the Global South. Some are functioning democracies, others are flawed democracies while others are kingdoms, theocracies, or authoritarian states.

Various scholars have critiqued this oversimplification, which fails to capture the complexities of these countries. As Timothy Shaw observes, the term Global South, despite its popularity, is “an unsatisfactory catch-all phrase which is neither geographical nor necessarily representative of the realities of power and diversity within the developing world”. Others argue that use of the Global South typology is a false narrative to pit a fabricated Global South against the West.

In reality, the Global South encompasses countries with different degrees of economic and political development, from emerging markets like Brazil and India to less developed nations in Sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, the political systems within these countries range from liberal democracies to autocratic regimes. This diversity complicates the idea of a unified Global South that can collectively support the LIO.

Among this motley crew of developing states, there are varying degrees of support for the current liberal hegemon of the existing LIO. According to the June 2023 PEW survey on opinions of the U.S., we see those developing countries that have favorable views of the U.S. For example, 74 percent of Nigerians, 63 percent of Brazilians, 65 percent of Indians have favorable views of the U.S.

Another survey was conducted for the Stanford Center on ‘China’s Economy and Institutions’ by the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research on “How Do the Chinese People View the “West”? Divergence and Asymmetry in China’s Public Opinion of the U.S. and Europe,” they found 29 percent and 49 percent of Chinese polled have somewhat unfavorable or unfavorable views of the U.S.

The Afrobarometer re-enforces the plurality of views on the US and the current LIO showing in an April 2023 poll that both China and the U.S. is losing popularity in Africa. In short, the Global South as a constructive and contributing unified actor in international relations remains tenuous at best for a variety of reasons stemming from its heterogeneous membership.

Institutional Weaknesses and Poor Governance

In terms of contributing to the LIO, institutional weakness and poor governance are limiting factors in the Global South’s ability to be a critical united force. Good governance, characterized by transparency, accountability, adherence to the rule of law, and effective institutions, is a precondition for meaningful participation in the LIO. However, many countries in the Global South grapple with corruption, weak rule of law, and institutional fragility. These problems impede these nations’ capacity to fully engage in the LIO, and to contribute constructively to global decision-making and dialogue.

Corruption, and the absence of effective rule of law and accountability mechanisms not only hinder economic development and social progress, but also discourage foreign investments, thereby further isolating these nations from the international community. It has been shown repeatedly that institutional weakness and corruption undermine economic growth, deter foreign investment, and limit social development. These issues hamper their ability to uphold the norms and principles of the LIO and pose significant challenges to the Global South’s integration into the LIO.

To illustrate, according to Transparency International surveys on corruption, the “Global South” countries continue to find themselves at the bottom end of the ranking system. The organization’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) showed that “124 countries have stagnant corruption levels, while the number of countries in decline is increasing. This has the most serious consequences, as global peace is deteriorating and corruption is both a key cause and result of this.”

The ability for the Global South to contribute to the liberal or other international order, an order made of rules, is proportional to the order these states can deliver to their domestic constituents without the use of violence or state coercion.

The World Bank’s 2023 Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA) argues for best practices in developing countries that effectively deal with inflation, currency management, financing, growth, social protection, transparency, and accountability and require robust and sustained institutional investment. Western countries can create a platform for states in the so-called Global South to do more in contributing to the LIO by enhancing good governance and institutional integrity.

Economic Instability and Dependency

Economic instability and dependency on developed countries further limit the Global South’s capacity to support the LIO. The COVID-19 pandemic and war in Ukraine has further amplified economic and food insecurities among developing countries.

This is unfortunate as many of these countries are heavily dependent on external aid or remittances, which can lead to economic vulnerability. In addition, their economies are often reliant on a limited range of exports, making them susceptible to global market fluctuations. This economic instability and dependency undermine their bargaining power in international negotiations, limiting their ability to shape the LIO in ways that reflect their interests and needs.

By way of example, food security in many African countries has been impacted negatively by a disruption in grain supplies and fertilizers inculcating more economic insecurity into the daily lives of ordinary citizens. With already a track record of poor governance and weak institutions, developing countries are not able to adeptly manage their own economic and food security issues. This has the effect of pushing citizens to rely on informal networks and corruption to secure food and money for their families.

Absence of a Common Political Identity

The absence of a common political identity or shared strategic interests among Global South countries impedes their ability to form a unified front in support of the LIO. In fact, countries identifying with being part of the Global South such as India and China have competing visions of who should lead the Global South and what its relationship should be with the U.S. and the West. China sees the Global South as a useful grouping to rally against the U.S. and the West in its efforts as Tsinghua University’s Yan Xue Tong writes:

“China will work hard to shape an ideological environment conducive to its rise and counter Western values. For example, the United States defines democracy and freedom from the perspective of electoral politics and personal expression, while China defines democracy and freedom from the perspective of social security and economic development. Washington should accept these differences of opinion instead of trying to impose its own views on others.”

In contrast, India as Ashley Tellis wrote in his recent Foreign Affairs essay titled “America’s Bad Bet on India: New Delhi Won’t Side With Washington Against Beijing”, India is charting out its own future; prioritizing a multipolar world in which India is a major player and a representative of the Global South not necessarily the leader of the Global South.

Part and parcel of that objective is not deferring leadership to China in the Global South or in organizations such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) or enlarged BRICS grouping by joining these organizations to ensure they do not proceed on a trajectory contrary to India’s interests.

Unlike the Global North, which has shared political and economic interests and is institutionalized in groups like the G7 or NATO, the Global South lacks similar cohesive structures making it an ineffective and divided actor in supporting or resisting the LIO.

Strengthening Western Economies: A Pragmatic Approach

Given the aforementioned challenges associated with the Global South concept and its unity, I argue that strengthening Western countries economically, diplomatically, politically, and in terms of security is a pragmatic approach to preserving and enhancing the LIO. This does not suggest a dismissive stance towards the Global South, but rather recognizes the need for a robust core of nations capable of driving reforms and fostering dialogue within the LIO.

Economically strengthening Western nations goes beyond ensuring a competitive edge; it also involves creating the capacity to assist other nations in their development efforts. A financially robust West can provide aid, technology transfer, and investment, aiding Global South nations in overcoming their developmental challenges.

The Japan-EU Infrastructure and Connectivity Agreement, the Supply Chain Resilience Initiative (SCRI) between India, Japan and Australia, and initiatives deployed through the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue or Quad are concrete examples of the kind of minilateralism that is needed to focus resources on developing countries and their development needs while at the same time using their comparative advantages to build more dynamism into their economies by helping build infrastructure and connectivity. This would inculcate more strategic autonomy into these regions through more robust growth and forming economic partnerships.

Expanding trade partners in 21st century trade agreements such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) to include more members creates virtuous economic activity that strengthens the West’s collective ability to compete with authoritarian regimes.

Similarly, the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) is an inclusive, a-la-carte economic framework that includes four core sets of issues organized across four verticals, or Pillars. These overarching Pillars encompass a large variety of issues in Trade, Supply Chains, Clean Economy, and Fair Economy, respectively.

If successful, the IPEF’s efforts will produce a new generation of economic and business rules for the Indo-Pacific region. As Palit and Iyer write “rules implemented across the Indo-Pacific – the most economically vibrant region of the world-can, over time, become global rules in their respective spheres. As some of the world’s largest and major economies-both developed and developing-start engaging economically on a common set of rules, the latter can evolve into benchmarks for upcoming as well as existing economic frameworks.”

Diplomatic and Political Strengthening of Western Nations

In addition to economic bolstering, the diplomatic and political strengthening of Western nations is paramount. The LIO is predicated on multilateral diplomacy and the promotion of democratic values. Western nations, with their longstanding democratic traditions and substantial diplomatic networks, are ideally positioned to champion these efforts.

The fortification of diplomatic ties and political stability in Western nations can also promote a more inclusive dialogue within the LIO. It can facilitate the sharing of best practices and capacity-building efforts in the Global South.

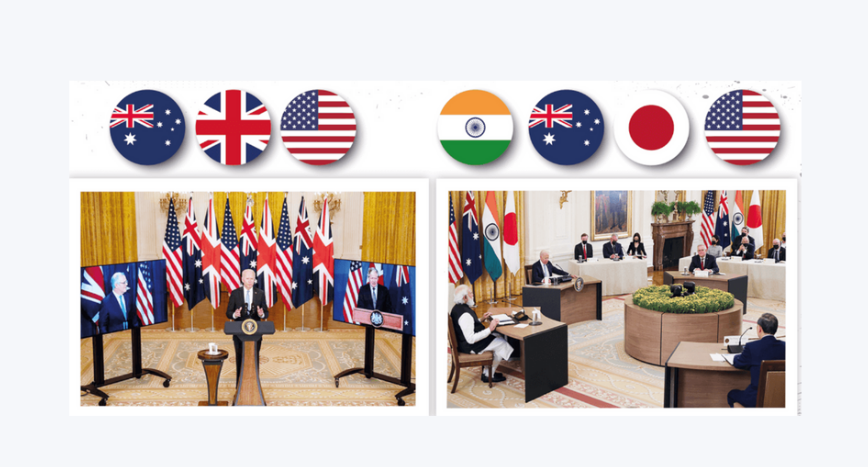

Investing in more problem-solving minilaterals are part of the self-strengthening process. Large scale multilateralism, whether it be through ASEAN, the G-20, EU or UN have fallen prey to the lowest common denominator of agreement. Innovative new problem solving minilaterals such as the Quad, AUKUS, the SCRI, and the latest Japan-South Korea-U.S. partnership based on the Camp David Principles are examples of designing Western cooperation in particular functional areas to deliver meaningful and sustained results. These minilaterals can and they do deliver their cooperation in various spheres and in various regions depending on the area of functional cooperation.

The Quad, for instance, is working on emerging technologies, COVID-19 and health security, infrastructure and climate change. AUKUS in contrast is focusing on AI, quantum computing, hypersonic technologies, and deterrence with the objective of ensuring emerging technologies are governed by rule of law and transparency. SCRI is providing the infrastructure and connectivity needed for sustainable development and the new agreement between Seoul, Tokyo, and Washington aims to deal with the security challenges associated with weapons proliferation on the Korean Peninsula as well as other contingencies in the Indo-Pacific.

Security Strengthening: Maintaining Stability in the LIO

Lastly, the strengthening of security in Western nations is crucial in maintaining LIO stability. Responding to global threats such as terrorism, cybercrime, and climate change necessitates a comprehensive and coordinated approach. The advanced military capabilities and technological prowess of Western nations play a pivotal role in this regard.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has demonstrated that great powers like Russia are willing to use military force to achieve their political objectives. Most recently, the Hamas, although a non-state actor, has demonstrated it is willing to inflict terror and carnage on its neighbor Israel to promote its cause. Many in the region echo Japan’s Prime Minister Kishida Fumio comments at the 2022 Shangri-la Dialogue, “Ukraine may be the East Asia of tomorrow.”

Only through building strong deterrence capabilities, robust minilateral and multilateral diplomacy amongst like-minded countries can the West protect the LIO. To get a buy-in for this order, they will need to enhance their capabilities comprehensively, build and deepen existing partnerships and importantly be consistent on when and where they deploy those resources.

Conclusion

The concept of the Global South is flawed due to its oversimplification of the heterogeneity and complexities within these countries. The institutional weaknesses, poor governance, economic instability, dependency and the absence of a common political identity within these nations further limit their capacity to support the LIO. While it is crucial to engage with these countries and support their development, it is equally important to acknowledge these limitations. The future of the LIO depends on a realistic understanding of the Global South and strategies that address these challenges.

This chapter does not seek to downplay the importance of the Global South’s engagement in the LIO. Instead, it argues for a balanced, pragmatic approach that acknowledges the Global South’s heterogeneity and challenges while recognizing the critical importance of strengthening Western countries. This approach does not negate the role of the Global South but rather seeks to reinforce the foundation of the LIO and create a more conducive environment for dialogue, cooperation, and mutual growth.

Preserving and strengthening the LIO is about creating an international order that is open to evolution and dialogue, capable of addressing global challenges, and committed to shared prosperity. To achieve this, it is vital to ensure that all nations, regardless of their geographical or economic position, are equipped to contribute to this common endeavor. Therefore, the strengthening of Western nations economically, diplomatically, politically, and in terms of security is not merely an option, but a necessity for the future of the LIO.

Download my chapter at:

Read more at:

Source: https://www.isdp.eu/publication/in-defense-of-the-liberal-international-order/

Leave a comment