Listen to the article

Critics of Japan’s Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) vision conflate it with an anti-China containment strategy. They see it as an extension of the former Trump administration’s Indo-Pacific strategy. Others see the “free and open” aspect of FOIP as hypocritical as Japan actively courts non-democratic states to support its FOIP vision, such as through the recent Japan-Vietnam summit and activities with countries considered flawed democracies, such as India.

These interpretations misread FOIP’s strategic imperatives.

First, conceptualizing FOIP as an anti-China containment strategy overlooks deep and mutually beneficial Sino-Japanese economic ties. To illustrate this, in 2020, a year in which China’s unfavorably ratings remained at record lows in Japan, we saw deepening Japanese exports to China, equivalent to $141.6 billion (and 22.1% of total Japanese exports).

If we include the $44.4 billion (6.9%) of Japan exports to Taiwan and the $32 billion (5%) of exports to Hong Kong, exports to greater China represent at least $218 billion or 33.1% of Japan’s total exports, nearly twice that of the US at $118.8 billion (18.5%). Economic decoupling is not possible nor desirable, a sentiment shared by most of China’s trading partners.

We have also seen Japan’s willingness to cooperate with China on infrastructure and connectivity in third countries based on the principles of transparency, fair procurement, and economic viability, to be financed by repayable debt and to be environmentally friendly and sustainable.

In surveys conducted by the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC), China returned to its position as the most promising country in terms of trade in FY2020 survey.

Its return to the top of the JBIC survey ranking was related to COVID-19 policies that kept supply chains mostly intact and operational, allowing for the resumption of economic activity. China compared very favorably to India, which experienced a severe nationwide lockdown and the associated disruption in the economy.

Second, FOIP’s “free” and “open” do not reference democracy or freedom of press advocacy; they refer to trading regimes, sea lines of communication, and the digital economy being rules-based, transparent, and arbitrated by international law and/or multilateral agreements.

Japan has a long track record of working with partners regardless of their political system, commitment to democracy, or human rights track record. Japan-Iran, Japan-Vietnam, and Japan-China energy and economic cooperation are cases in point.

Participating in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement alongside China further illustrates Japan’s reticence to sever its economic ties with its largest trading partner.

Third, Japan’s expanded defense procurement continues to be incremental both in terms of budget but also capabilities. For example, according to Janes Defense Budgets forecasts an increase to $49.6 billion in 2022 is slightly larger than 1% of Japan’s GDP.

Compared to China, spending approximately $209.16 billion in 2021 (approximately 1.34% of GDP), Japan’s spending increase remains modest and focused on the acquisition of cyberspace, electromagnetic, and over-the-horizon radar capabilities, as well as satellites to enhance space and maritime domain awareness.

Beyond these capabilities, the 2022 defense budget aims to secure funding for the deployment of around 570 Japan Ground Self-Defense Forces (JGSDF) and to deploy surface-to-air and anti-ship missile batteries on Okinawa’s Ishigaki Island.

In contrast, while China is committed to expanding its nuclear arsenal and testing hypersonic delivery systems, Tokyo is still wrangling over constitutional reform and whether it should increase defense spending to 2% of GDP.

If FOIP was a containment strategy, we would see a substantial increase in deterrence capabilities, including submarine acquisitions, lethal autonomous weapon systems (LAWs), and the acquisition of mid- to long-range missile systems that would be able to target threats in the region.

Instead, Tokyo’s FOIP vision continues to be multifaceted. Key features continue to include trade promotion, development, the expansion of infrastructure and connectivity, and investment in resilient supply chains. Together, these core features are inculcating a rules-based predictability into critical sea lines of communication (SLOCs) through an adherence to international law.

For Tokyo, the focus on SLOCs, trade promotion, development, the expansion of infrastructure and connectivity and investment in resilient supply chains is tangentially related to Japan’s economic security. A disruption in SLOCs through a regional conflict, incident, or Taiwan contingency would cut off Japan’s economy from the critical arteries for the import and export of goods and energy resources.

Trade promotion, development, the expansion of infrastructure and connectivity and investment in resilient supply chains is about enmeshing Japan into the Indo-Pacific’s economy, its burgeoning institutions, and its rules-making process.

Tokyo wants to lock itself into the region’s political economy to ensure that it evolves in a form favorable to Japanese interests. This means strategic partnerships, multilateral cooperation and agreements, and socio-economic tools rather than military tools being the primary means Tokyo wishes to achieve its strategic priority.

The Japan-EU Economic Partnership, Japan-EU Infrastructure and Connectivity agreement, and the Resilient Supply Chain Initiative (RSCI), which include Japan, India, and Australia, are all examples of Tokyo’s efforts to enmesh itself in a series of multilateral agreements that anchor Japan into the national interests of other regions and countries and to anchor those countries and regions into the Indo-Pacific.

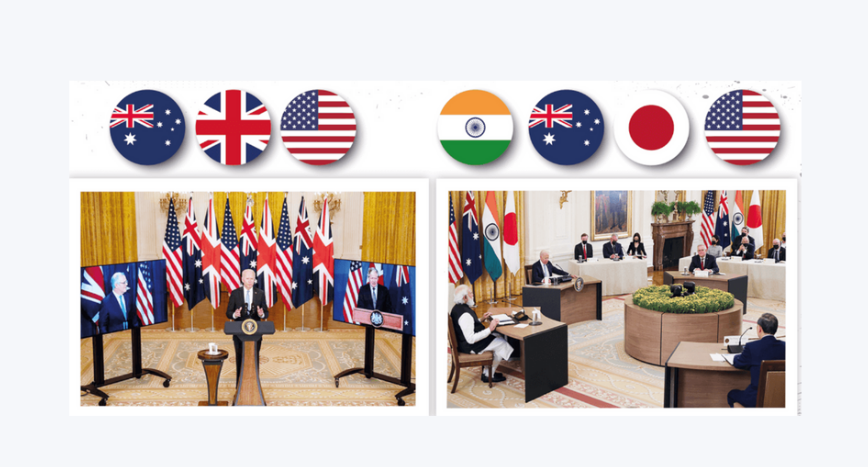

This multilateral approach does not eschew strategic partnerships, defense agreements, and the centrality of the Japan-US alliance in Japan’s FOIP vision. Japan is continuing to deepen its relationship with the US while moving towards a defense treaty with Australia.

Discussions are also on their way towards the Japan-UK Reciprocal Access Agreement, 2+2 ministerial security talk between Japan and France, and on May 3, 2021 Japan and Canada announced their “Shared Japan-Canada Priorities Contributing to a Free and Open Indo-Pacific.”

The latter announcement stresses cooperation in six key areas including: 1) the rule of law; 2) peacekeeping operations, peacebuilding, and humanitarian assistance and disaster relief; 3) health security and responding to COVID-19; 4) energy security; 5) free trade promotion and trade agreement implementation; and 6) environment and climate change.

This is an agenda that speaks to Japan’s comprehensive approach to achieving a free and open Indo-Pacific region. It also illustrates the limits of a securitized Japanese FOIP vision focused on confronting or containing China directly.

Policymakers in Washington should understand that Japan’s FOIP approach resonates with many regional stakeholders in the Indo-Pacific as it aims to invest in regional institutions such that they are more resilient, transparent, and rules-based.

Critically, Japan continues to engage with China economically from a position wedded to both multilateral engagement and deepening cooperation within the US-Japan alliance.

This article was first published on January 6, 2022, at https://mailchi.mp/pacforum/pacnet-1-the-limites-of-a-securitized-japanese-foip-vision-1172683?e=79d5c78d1c.

Leave a comment