Japan has wedded its Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) Vision to various initiatives, including the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), to embed itself in the regional political economy. However, several factors such as COVID-19, geopolitics, policy choice, and costs are shaping Japan’s engagement. The IPEF is an inclusive agenda that sets rules and lays the foundation for the American-led economic framework, anchoring the United States (US) in the region. It should be viewed through several initiatives, including the Resilient Supply Chain Initiative (RSCI), Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT), and the Japan-European Union (EU) Economic Partnership Agreement (EPA) amongst others. The Japan-US alliance informs all aspects of the Indo-Pacific engagement, but Japan has its own nuanced view of the region. Japan seeks to build resilience into the relationship with China through selective diversification and economic engagement while rejecting zero-sum approaches, decoupling and containment policies toward the world’s second largest economy.

Introduction

Japan’s interest in the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity (IPEF) stems from its strategic priorities to maintain economic growth and economic security in the region. These strategic priorities are based on two realities.

First, the economic relationship between Japan and China. In 2021, bilateral trade relations reached a record high of US$391.4 billion (S$524.9 billion) for the first time in 10 years since 2011, according to the Japan External Trade Organization (JETRO). Chinese state-run newspapers like China Daily and Global Times highlighted the fact that Japan and China are not only neighbours but also inseparable economic partners, with more than 30,000 Japanese companies active in China.

Second, despite China’s disapproval of Japan’s involvement in the IPEF, which China views as posing risks to Japan’s economic and trade cooperation4 not only with China but also with the United States (US), Japanese businesses hope that their participation will lure the US back to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) or a Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) 2.0 led by the US. According to Japan’s Foreign Minister Yoshimasa Hayashi, it is the US that shaped the TPP into its current form of strategic importance and therefore, the US should return to the broad cross-Pacific free trade agreement.

To achieve these strategic priorities, the Kishida administration is practising economic realism, which suggests that the maintenance of the seikei bunri (separation of politics and economics) relationship with China at the highest levels of government seems unlikely. The use of nationalism in both China and Japan to consolidate political support for the current leadership makes it difficult for political leaders to return to conducting bilateral relations with a singularly economic focus. This shift is based on a growing track record of economic coercion, supply chain disruptions, weaponisation, and erratic policy decisions in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is also related to the energy and food security-related issues that emerged following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022.

For Tokyo, the IPEF represents a new era of economic engagement driven by concerns about economic security, resilience, and the prioritisation of rule-setting in the areas of trade, supply chains, clean economy and fair economy.

Through the IPEF, Japan hopes to inculcate the US into the Indo-Pacific region, build shared institutions and norms, and strengthen its economic synergies with the region for bolstering its economic security and resilience vis-à-vis China while staying economically engaged with the latter. As a US-led, China-excluding coalition, the IPEF could also have a major impact on the Japanese economy by encouraging member countries to leave or decrease their economic reliance on China.

This paper examines Japan’s strategic priorities pertaining to the IPEF, their connection to Japan’s relationship with China and the US, and the actions being taken for successful implementation of the IPEF.

Why does the IPEF matter to Japan?

Japan’s interests in the IPEF can be traced back to its long-standing commitments to free trade and open markets. Since it became a major trading nation in the late 1800s, with limited natural resources, Japan has relied heavily on international trade to fuel its economic growth. This reliance has necessitated a rules-based order and access to resources and consumer markets.

With the US stepping away from the TPP in January 2017, Japan and other TPP partners were left standing at the trade altar. Even though the possibility was unlikely, many had hoped that the US would return to the TPP. In an exclusive interview with CNBC and Broadcast Satellite Japan, former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said, “Since the US understands the importance of having free and fair trade rules, it is our wish, by all means our strong wish is that the US will return to TPP.”

The Biden administration, understanding that advocating for joining the CPTPP was a non-starter for the US due to domestic political divisions, launched the IPEF in May 2022 with 14 diverse partner countries representing 40 per cent of global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and 28 per cent of global goods and services.

Despite not discussing market access, the IPEF offers numerous advantages to its members that distinguish it from traditional trade agreements. These include the ability for IPEF participants to choose from a range of initiatives falling under the IPEF umbrella, as well as its focus on trade, supply chains, the clean economy, and a fair economy. The emphasis on these areas aims to promote sustainable economic growth and development for all participating countries. The à la carte approach to the IPEF membership ensures that states with different politico-economic systems and at different levels of development can join the Framework without being compelled to adopt all parts of the initiative. This feature contributes to the IPEF’s inclusivity.

The four pillars of the IPEF are core foundations for stable and rules-based growth in the region that will translate into a clean, green, resilient, technological, and fair economy.

The Trade Pillar stresses “trade and technology policies that advance a broad set of objectives and that fuel economic activities and generate investments; promote resilient, sustainable, and inclusive economic growth and development; and benefit workers, consumers, indigenous peoples, local communities, women, and micro-, small-, and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs).” The Pillar links the growing theme of economic security to technology and development to resilience. In the former, Tokyo sees its economic security related to being at the forefront of technological development and also in setting of rules for inculcating these technologies into the Indo-Pacific’s economic growth. In the latter, the Pillar links development to building resilience into economies reducing their vulnerabilities to economic destabilisation from financial crises, natural disasters, supply chain breakdowns, or economic coercion by other states.

The Supply Chains Pillar aims to “ensure secure and resilient supply chains and to minimise disruptions and vulnerabilities, which may require evolving our public institutions and improving coordination with the private sector. Recognising the different economic characteristics and capacity constraints of Members, we seek to coordinate crisis response measures and to expand cooperation to better prepare for, and mitigate the effects of, disruptions to better ensure business continuity and improve logistics and connectivity, particularly in critical sectors.”

The realisation of acute vulnerabilities of an overconcentration of supply chains in one country is related to economically coercive behaviour, conflict, and erratic policy choices in China over the COVID-19 pandemic. With regard to economic coercion, Japan, South Korea, Australia, Canada, Taiwan and other states have experienced coercion by China, and see selective diversification of supply chains as being essential for building resilience into their economies.

Conflict – current and possible in the case of Taiwan – also weighs heavily in the minds of Japan and other IPEF members. The downstream effects of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on food security and energy security have amplified concerns about global supply chains with Prime Minister Kishida Fumio stressing “today’s Ukraine could be tomorrow’s East Asia”, an indirectly labelled concern about China’s assertive behaviour and militarisation in the region as threats towards Taiwan. The supply chains disruptions experienced after the COVID-19 pandemic and those associated with China’s Dynamic Zero COVID-19 policies have also led to the realisation that politically-based policy choices within China can destabilise supply chains prompting the IPEF members to diversify, build resilience and de-risk from volatile policy environments.

The Clean Economy Pillar aims to promote “clean energy transitions, scaling and reducing the cost of innovative technologies, and advancing low greenhouse gas emissions in priority sectors. Specifically, the proposal seeks to create a framework through which [the] IPEF [p]artners can identify new opportunities and advance existing efforts in shared areas of interest to promote the resiliency, innovation, sustainability, and security of a clean economy and to support ongoing collaboration among IPEF Partners and stakeholders.” The Pillar recognises that sustainable and environmentally friendly growth is a prerequisite for developed and developing nations with many of the latter (for example, the Pacific Island countries) facing existential climate change challenges.

Lastly, the Fair Economy Pillar recognises that “fairness, inclusiveness, transparency, the rule of law, and accountability are essential to improving the investment climate, ensuring shared prosperity, and promoting labo[u]r rights based on the ILO Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work, which the Partners have adopted.” Overlapping with the labour components of the CPTPP, the Pillar aims to create a level playing field for the IPEF members, for ensuring economies compete on mutual understanding of labour rights and the necessity to invest in greener and labour-friendly economic practices.

Multi-layered approach to Indo-Pacific economic engagement

Japan’s support for this initiative was unsurprising given its abiding interest in promoting a rule- based order through the Free and Open Indo-Pacific Vision (FOIP) since its inception in 2017. Recently, Japan has updated the FOIP through its “New Plan for a Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP)”, which includes enhancing the connectivity of the Indo-Pacific region and fostering the region into a place that values freedom and rule of law, is free from force or coercion, and prosperous.

The Economic Partnership Division under the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) of Japan described the IPEF as a new approach to regional collaboration, where diverse countries from the region work together to create a balanced package between rules and cooperation, and tackles contemporary issues such as digital economy, strengthening supply chain resilience, decarbonisation and clean energy. As such, Japan will cooperate with individual countries to realise innovative, inclusive, and sustainable economic growth in the Indo-Pacific region.

A key driver of Japan’s interests in the IPEF is the growth of the digital economy. Tokyo views the digital economy rapidly becoming a key contributor of economic growth and job creation. It also sees the global digital economy as underregulated and believes the IPEF will be useful in allowing Japan, alongside like-minded members within the IPEF, to be the first movers in standard- setting for laying ground rules on operations of the digital economy, the relationships of data with data protection, and between government and citizens’ data.

Japan recognises the importance of the digital economy and is keen to ensure that it can fully participate in this growing sector. Another key driver of Japan’s interests in the IPEF is the increasing importance of data in the global economy. With data becoming a key asset in the global economy, and the ability to collect, analyse, and utilise data becoming increasingly important for businesses and governments alike, Japan is committed to fully participating in the global data economy while maximising the benefits that data can provide.

Essentially, by participating in the IPEF, Japan aims to promote the digital economy and ensure the free flow of data across borders. This goal encompasses the advancement of digital infrastructure, such as 5G networks and data centres, as well as the development of digital technologies and services.

Japan’s strategic priorities

Japan has for long been a regional economic power. However, its economic growth has slowed considerably in the current century, particularly in the last decade, with the economy contracting sharply after the COVID-19 pandemic. To sustain its economic position and achieve sustainable economic growth, Tokyo has sought to increase economic ties with other countries in the region through multiple trade agreements and economic partnerships such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the CPTPP, and the Japan-European Union (EU) Economic Partnership. The US has been noticeably absent from all these agreements.

The IPEF, tabled by the US, aims to promote economic cooperation in the Indo-Pacific, as well as advance objectives that are congruent with Japan’s economic and national security interests.

A major strategic priority for Japan is maintaining its security in the region. Japan is geographically vulnerable, with China to the west and North Korea to the north. In recent years, China has challenged the rules-based order in sea lines of communication in the South China Sea, the Taiwan Strait, and the East China Sea. Collectively, these critical arteries transport approximately US$5.5 trillion (S$7.3 trillion) in imports and exports annually. They also transport critical energy resources fuelling the Japanese, Chinese and the South Korean economies. This has led Japan to seek closer security ties with the US and other countries in the region.

Japan also prioritises enhancing regional connectivity, particularly in the Indo-Pacific region, to facilitate trade and investment. To achieve this goal, Japan is keen on promoting the development of physical infrastructure, such as ports and airports, and digital infrastructure, including high-speed internet connections. To sum up, Japan’s strategic priorities include sustaining economic growth, maintaining regional security and the rules-based order.

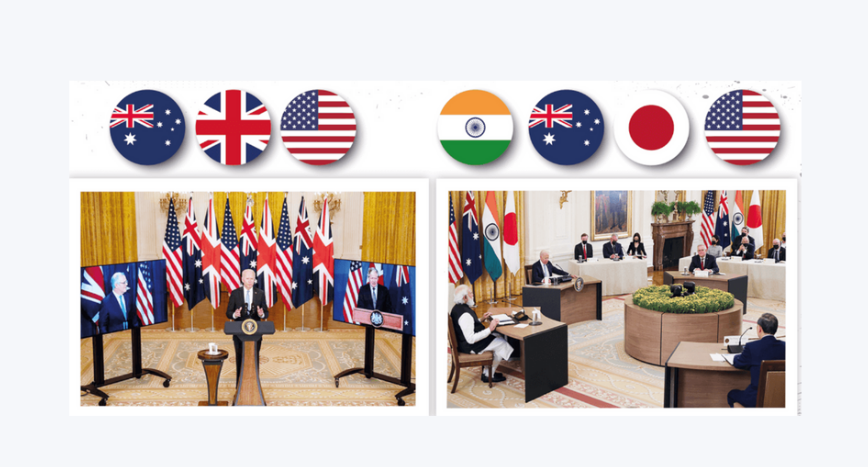

Japan’s strategic priorities in relation to its relationship with China and the US

Relationship with China

Japan’s relationship with China is complex. The two countries have a history of conflict, dating back to the second Sino-Japanese War in the 1930s and 1940s. More recently, tensions have risen over territorial disputes in the East China Sea. However, Japan also has a significant economic relationship with China, with Beijing being its largest trading partner. Additionally, China is also the top trading partner for more than 120 countries.

Japan’s engagement in the IPEF has implications for its relationship with China, given that China is a key player in the Indo-Pacific region and is not a member of the initiative. This has led some to speculate that the IPEF aims to contain China’s economic influence in the region. Launched in Tokyo, the IPEF excludes China and some of its close Southeast Asian partners such as Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar, not least because the IPEF is meant to counter the geo-economic rise of China. However, Japanese officials have denied this, stating that the initiative is open to all countries that share its goals of promoting economic cooperation and connectivity in the region based on a common set of transparent rules.

Japan’s participation in the IPEF can be seen as a way to promote economic growth and regional supply chain connectivity without over-reliance on China. Hence, the IPEF’s design aligns with Japan’s vision and targets the wider Indo-Pacific region, rather than focusing solely on Japan and China. By promoting regional connectivity through the Indo-Pacific Framework, Japan can reduce its dependence on China and promote greater economic and political diversity in the region.

Simultaneously, Japan’s interest in the IPEF is not necessarily incompatible with its relationship with China. Both Japan and China recognise the importance of the digital economy and the free flow of data, and both nations are making substantial investments in these domains. Japan’s interest in the IPEF may provide an opportunity for greater cooperation between Japan and China in these areas. This can be carried out through positioning of Tokyo as a digital economy norm-maker within the IPEF which create conditions that may shape Beijing’s digital economy standards and regulations so that they are more in-line with IPEF members.

Relationship with the US

Japan’s relationship with the US is also important in the context of the IPEF. The US has historically been Japan’s closest security ally, and the two countries have a strong economic relationship. In 2022, Japan enjoyed a US$47 million (S$63 million) trade surplus with the US but registered a US$42 million (S$56.3 million) deficit with China. The election of Donald Trump as US President in 2016 had brought some uncertainty to the relationship, as Trump was critical of Japan’s trade policies and called for Japan to pay more for its own defence.

Despite these challenges, Japan has continued to prioritise its relationship with the US. The two countries have a shared interest in maintaining stability in the region, and Japan sees the US as an important partner in countering China’s assertiveness. In addition, Japan has sought to strengthen its economic ties with the US through initiatives such as the US-Japan Economic Dialogue,65 which was launched in 2017.

Japan’s interest in the IPEF can be seen as a tool to promote greater economic cooperation and supply chain connectivity with the US. The IPEF is designed to promote economic growth and regional supply chain connectivity across the Indo-Pacific region, including between Japan and the US.

By promoting greater economic cooperation and supply chain connectivity through the IPEF, Japan can strengthen its relationship with the US and promote greater economic and political stability in the region.

Japan’s involvement in the IPEF can be interpreted as an attempt to anchor the US into the region through shared trade priorities.

Overall, Japan recognises the importance of maintaining good relations with both the US and China. The IPEF provides a framework for greater cooperation with the US and the IPEF partners while it concurrently continues to engage with China through the RCEP.

Japan’s concrete steps to translate the IPEF into reality

Japan has taken several concrete steps to ensure the realisation of the IPEF. By way of example, Japan has the capacity to transfer capabilities for managing and strengthening supply chains in the manufacturing sector and infrastructure projects, making it well-suited to support sustainable development efforts around the world. Japan hosts the Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD), which provides an open forum for stakeholders to engage in innovative discussions related to African development programmes.

Since its inception in 1993, TICAD has made significant contributions to socio-economic development in Africa through aid grants and technical assistance. Another important initiative is the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure (PQI), which was launched by Japan in 2015. The PQI aims to promote high-quality infrastructure development in the region, with strong emphasis on transparency, openness, and sustainability. One aspect of this Partnership is the focus on quality. The PQI sets itself apart by prioritising the quality of investments over quantity. This approach ensures that investments are made with a long-term perspective, taking into account the sustainable development character of the projects.

The Government of Japan has committed to investing US$110 billion (S$148.7 billion) for quality infrastructure investment in Asia over the next five years, in collaboration with the Asian Development Bank (ADB). According to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, this investment is expected to have a catalytic effect on mobilising financial resources from private companies around the globe to support Asia’s development needs.

To this end, Japan will expand and accelerate assistance through a range of organisations and aid tools, while also enhancing the role of the Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) and strengthening collaboration with the ADB. By leveraging its expertise and resources, Japan is well-positioned to play a leadership role in promoting sustainable economic development in a multipolar Indo-Pacific. Furthermore, environmentally sustainable infrastructure investment initiatives can complement the environmental initiatives associated with Pillar 3 of the IPEF.

In addition to these initiatives, Japan has sought to strengthen its economic ties with other countries in the region through bilateral and multilateral trade agreements. One of the most significant is the CPTPP, which was signed in 2018 by 11 countries, including Japan. With member countries representing 13 per cent of the global GDP, the CPTPP is a landmark agreement that aims to lower trade barriers in goods and services, promote economic cooperation, and enhance regional integration. It is noteworthy that Japan played a significant role in saving the TPP after the sudden withdrawal of the US under the Trump administration. Japan’s efforts to revive the Agreement demonstrate its commitment to promoting free trade and economic development, even in the face of significant challenges and uncertainties.

The IPEF proposed by the US and the FOIP strategy introduced by Japan both aim to address China’s growing influence in the region. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a massive infrastructure development project, has been a cause for concern for many countries in the region, including Japan and the US.

China’s BRI has been criticised for its lack of transparency, the potential to create debt traps for developing countries, and strategic implications for China’s regional influence. In response, the IPEF and FOIP strategies seek to provide an alternative and more transparent approach to infrastructure development and economic integration in the region.

The IPEF and FOIP strategies prioritise the development of quality infrastructure that is sustainable and benefits local communities. This contrasts with China’s BRI, which has been criticised for focusing on low-quality infrastructure that may not be sustainable in the long term.

By focusing on quality infrastructure, the IPEF and FOIP strategies seek to promote economic development that benefits all countries in the region, rather than just China. The IPEF and FOIP strategies also emphasise the importance of regional connectivity and integration through the development of transport infrastructure such as ports, airports, and highways, to facilitate trade and economic growth. By promoting regional connectivity, the aim is to reduce barriers to trade and investment, which can help to counter China’s growing economic influence in the region.

Furthermore, both strategies recognise the significance of regional security in promoting economic development and connectivity. This includes promoting the rule of law, freedom of navigation, and maritime security. By enhancing regional security, the strategies seek to counter China’s growing military assertiveness in the region and promote greater stability and cooperation among countries in the Indo-Pacific region.

Conclusion

Japan’s interests in the IPEF are driven by its strategic priorities to maintain economic growth and security in the Indo-Pacific region. Given Japan’s significant economic and security relationships with both China and the US, its involvement in the initiative is of significance. To ensure the realisation of the IPEF, Japan has already taken several concrete steps, including the development of initiatives such as the Asia-Africa Growth Corridor and the Partnership for Quality Infrastructure, as well as bilateral and multilateral trade agreements, including the CPTPP.

Although the IPEF is still in its early stages, Japan’s strong commitment to the initiative indicates that it is likely to maintain a leading role in the region’s economic and security landscape in the years to come. This follows Japan’s previous success in salvaging the TPP and negotiating the CPTPP.

Leave a comment