Listen to the article

Japan and China have a mutually beneficial economic relationship characterised by competition and cooperation. Their bilateral trade relationship increased from US$371 billion in 2021 to US$390 billion in 2022 despite the COVID-19 pandemic, deepening geopolitical tensions and mutual disapproval ratings reaching record levels.

Deep economic cooperation in the areas of manufacturing, technology and finance has coexisted awkwardly with decades-long political and territorial disputes between the two countries. This has led Japan to develop economic relations with China through a policy that separates politics and economics or seikei bunri.

Amid intensifying US–China strategic competition, China’s track record of economic coercion and its long-term objectives to secure its own ‘core interests’, Japan has become more concerned about its economic reliance on China. A result is that the seikei bunri principles for engaging with China economically are giving way to Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s new ‘economic realist’ diplomacy.

Japan’s economic relations with China are less easily separated from the political differences between the two countries. Policy approaches to address concerns about the impact of politics on Japan’s economic security include selective diversification of supply chains away from China, reshoring, friend- shoring and national technological development.

The drift away from seikei bunri has raised concerns in Tokyo about Japan’s vulnerability to economic coercion and the weaponisation of supply chains, particularly in prominent industries such as rare earth metals, electronics and automobiles. Political leaders in Japan have already committed significant strategic and financial resources to enhancing economic security through selectively diversifying supply chains and reducing reliance on China.

Initiatives include the adoption of supplementary budgets for economic security, such as securing domestic production bases for advanced semiconductors. Supplementary budgets have focused on promoting domestic investment to support supply chains and encourage their diversification. Despite the political and security complexities, the mutually dependent economic relationship remains largely intact, is deepening and highly complementary.

There is no replacing China as Japan’s major market for goods and services. Japanese companies have invested heavily in China, particularly in the automobile, electronics and machinery sectors. China is also a major source of low-cost goods and components for Japanese companies. This role has kept prices low and enhanced the competitiveness of Japanese products in global markets.

To decouple the Japan-China economic relationship would require untangling the complex and multifaceted mutual dependency that defines it, a relationship that comes with benefits and also with risks. Geopolitical pressures, the increased cost of doing business in China, economic development in Southeast and South Asia, COVID-19 and policy-induced disruptions to supply chains have contributed to Japan recalibrating its economic relationship with China to enhance its economic security.

Examples include supplementary budgets that aim to diversify some supply changes away from China and participate in trade agreements that include China such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership as well as those that so far exclude China such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership and the Japan-EU Economic Partnership Agreement.

But Japan also acknowledges the importance of maintaining economic ties with its largest trading partner and working together to promote regional economic growth and stability. After the end of the Cold War, seikei bunri policy was challenged by political and territorial disputes that have spilled over into the economic relationship. This resulted in investment restrictions, consumer boycotts, declines in tourism and tensions in industries such as steel, electronics and rare earth metals.

After taking office in October 2021, Kishida positioned economic security as a major focus of his administration based on assessment of the challenges associated with China’s rise in line with the previous Abe and Suga administrations. In the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine – with its impact on downstream energy and food security – Kishida warned that ‘East Asia could be the next Ukraine’.

Previously, Chinese economic coercion pressured Japanese corporations and policymakers to change tack on issues Beijing deemed important. Beijing restricted exports of rare earth metals, essential for many high-tech industries and imposed unofficial trade sanctions on Japanese companies. This pressure resulted in the release of a Chinese fisherman in 2010 and Japan’s nationalisation of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands in 2012.

Aside from territorial disputes, simmering political and historical tensions have intensified owing to China’s growing military assertiveness. Examples include military exercises around Taiwan in August 2022 and building and militarising islands in the South China Sea. Some measures have been taken to decrease Japan’s vulnerability to coercion by China and diversify its supply chains.

First, Tokyo is promoting reshoring, urging Japanese businesses to migrate their production back to Japan from China or to explore new production bases in Southeast Asia, India and other countries. The government has introduced policies to support companies that are considering reshoring, including subsidies, tax breaks and regulatory reforms.

Second, Tokyo has highlighted the importance of diversifying supply chains, particularly for key components and materials such as rare earth metals. Japan has been investing in alternative sources of rare earth metals, such as recycling and developing new mines in other countries. Japan is also exploring the use of new materials that can replace rare earth metals in some applications. It has worked with countries such as Canada to secure access to critical minerals.

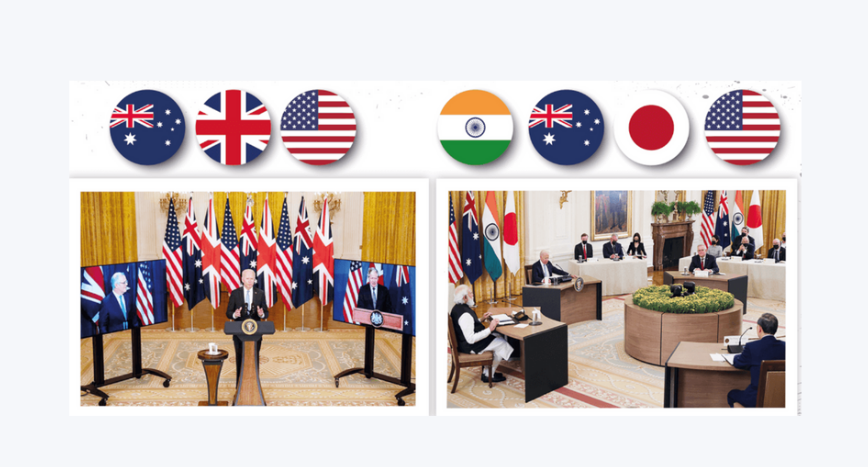

Third, Tokyo has encouraged collaboration to enhance economic ties and agendas under the umbrella of the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’. The G7 Foreign Ministers’ statement on 18 April 2023 – which stressed that ‘resilient supply chains should be built in a transparent, diversified, secure, sustainable, trustworthy and reliable manner’ – exemplifies this.

Finally, Japan has emphasised the importance of strengthening domestic industries. This includes the development of new industries and technologies expected to decrease Japanese vulnerability to China and deepen its economic security.

Tokyo has allocated funds for investment in the development of next-generation semiconductors, which are essential for many high-tech industries. Japan’s broader strategy is to enhance its economic security and reduce its vulnerability to geopolitical risks and uncertainties regarding rare earth metals, semiconductor materials, electronic components and batteries.

A critical component for Japanese businesses is semiconductor materials. Despite its role as a major producer of semiconductors, Japan continues to rely on imports of key materials from other countries, including China. These materials include parts such as silicon wafers, capacitors, resistors and printed circuit boards, as well as raw materials like lithium and cobalt.

To mitigate this vulnerability, Tokyo has directly courted the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, among others, to relocate to Japan. It has also been investing in the development of next-generation semiconductors and encouraging its companies to move up the value chain to reduce their dependence on imports.

In the area of rare earth metal extraction and export, China continues to enjoy a monopoly that makes Japan and other states vulnerable to rare earth supply chain weaponisation. This exposes signature Japanese industries including electronics, automobiles and renewable energy to possible coercion.

But developing alternative sources of rare earth metals is a complex and challenging task and Japan faces several obstacles, including limited domestic resources, high extraction costs, environmental concerns and a lack of downstream capability. As with energy and other mineral resources, Japan lacks domestic sources of rare earth metals and is reliant on imports to meet its needs. Developing new mines is difficult and expensive and there are few viable alternatives to China as a supplier.

Recent initiatives with Canada remain feasible but financially unviable. Cost efficiency remains an important factor for deleveraging from the comparative advantage that China continues to enjoy in extracting rare earth metals from ores inexpensively. The process requires specialised equipment and expertise and the price – equipment equation is a hurdle to developing alternative sources that compete with Chinese suppliers on price.

Aside from cost efficiency, environmental concerns linger over the impact of rare earth mining and processing, including the pollution of air and water and generation of waste. Developing new mines and processing facilities that meet environmental standards can be complicated and expensive. Resource-rich countries are often reticent to take on the environmental burden of resource exploitation. Developing alternative sources of rare earth metals requires not only the extraction and processing of ores, but also the development of downstream industries that can use the metals in products.

While Japan has a strong high-tech industry, developing new industries that use rare earth metals takes time and requires significant investment which may not meet the demands of the current market. Enhancing economic security and creating resilience against economic coercion and other forms of economic instability will be difficult. It will require the Kishida and future administrations to develop new mines and processing facilities for rare earth metals while meeting a range of environmental standards to ensure activities are conducted safely and sustainably.

Key areas of focus will include air and water quality control, waste management, biodiversity, and social and cultural standards. Japan’s experience in reviving its environment after years of fast and dirty growth in the postwar period suggests that it may be possible through unilateral and multilateral cooperation. For air and water quality standards, rare earth mining and processing can generate significant amounts of dust, carbon emissions and wastewater. Policymakers in Japan will need to establish standards for air and water quality to ensure that pollution is minimised.

The same is true for waste management standards. Studies have shown that rare earth mining and processing can generate large amounts of waste and tailings that contain radioactive materials and other pollutants. Japan will need to establish standards for waste management and ensure that waste is stored and disposed of safely. Rare earth mining risks negatively impacting biodiversity through the destruction of habitats and the introduction of invasive species. Biodiversity conservation standards will need to be established to ensure minimal impact to natural ecosystems.

Social and cultural standards must also be set up to avoid the potential negative ramifications of rare earth mining and processing. These include the displacement of local communities and the destruction of cultural heritage sites. Japan will need to carry out impact assessments and ensure that activities are conducted in a manner that respects the rights and interests of local communities. Developing new mines and processing facilities for rare earth metals will require careful planning, consultation and collaboration with stakeholders, including local communities, environmental groups and government agencies.

The Kishida administration is starting this process, working with Australia and African states, such as Namibia, in joint ventures. Japan’s efforts to reduce its dependence on China reflect a desire to enhance economic security and reduce vulnerability to geopolitical risks and uncertainties. With the shift to economic realism away from the principles of seikei bunri, the Kishida administration – and possibly future administrations – aims to balance economic opportunities with Japanese national interests in an increasingly complex and uncertain global environment.

This article was first published on October 12, 2023, at East Asia Forum

Leave a comment