Listen to the paper

The debate on the role and possible expansion of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) is growing. Is there a role for middle powers such as Canada in the Quad? This article examines possible Canadian participation in the Quad from the perspective of middle-power diplomacy.

Key lines of enquiry include identifying Canadian middle-power interests in the Quad, capabilities that Canada can bring to the Quad, and how to formulate participation.

Findings suggest that Canada’s potential Quad participation is limited by its capacities and that its middle-power contributions would be capability-focused, including enhancing maritime awareness and consensus building of the consultative process through proactive diplomacy.

Introduction

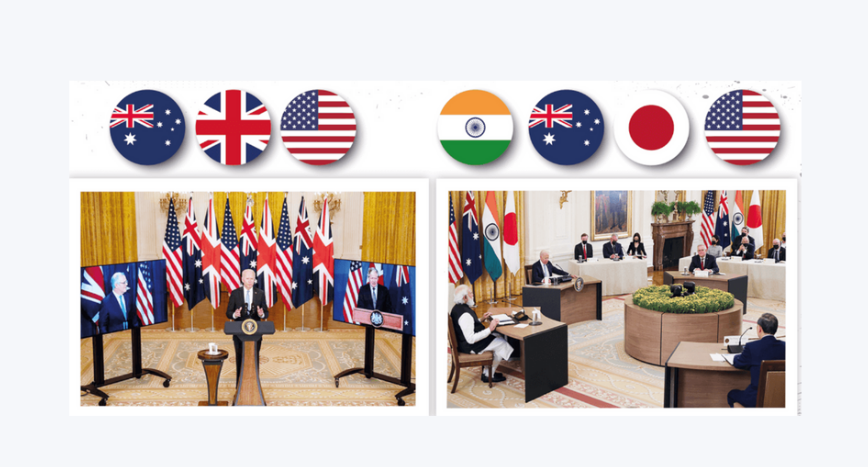

The Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) has its roots in the non-traditional security cooperation that transpired following the joint humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HA/DR) efforts, among Australia, Japan, India, and the United States, in the wake of the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami, which killed over 250,000 people throughout the region.

This joint operation laid bare the potential opportunities of participating states as to the possibilities that their quadrilateral cooperation could achieve. In May 2007, senior officials from Australia, India, Japan, and the United States, arranged an inaugural Quad meeting, on the sidelines of the ASEAN Regional Forum (ARF) meeting in Manila, Philippines, to discuss ways to take the four-power relationship forward. Ryosuke Hanada argues that while

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe gave birth to the idea of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue in 2007, that was based on incrementally expanded regional cooperation mechanisms, especially the East Asia Summit (EAS), and the development of triangular relations, especially Australia-Japan-US trilateral security cooperation. Both were, in different ways, stimulated by increasing threat perceptions of China based on uncertainties about China’s rise.

In that sense, the revival of the Quad in 2017 cannot simply be attributed to Shinzo Abe’s leadership but also to the fact that four governments carefully and steadily shifted their foreign policy priorities in broader East Asia or the Asia- Pacific and developed bilateral and trilateral security cooperation mechanism since 2007 in the face of a rising and assertive China.

Abe recognized these developments and skillfully helped revive the Quad in 2017 with his conceptualization of the Indo-Pacific regional concept as a pillar of Japanese foreign policy.

The debate on the role and possible expansion of the Quad is growing. Notwithstanding, while much has been written about the Quad, little has been written about the role of middle powers, like Canada, within this evolving institution. Is there a role for middle powers such as Canada in the Quad? If so, what are the parameters by which they should contribute to a Quad Plus arrangement?

This article examines Canadian participation in the Quad from the perspective of middle-power diplomacy. Key lines of enquiry include identifying Canadian middle-power interests in the Quad, capabilities that Canada can bring to the Quad, and how to formulate participation.

Findings suggest that Canada’s potential Quad participation is limited by its capacities and that its middle-power contributions would be capability-focused, including enhancing maritime awareness and consensus building of the consultative process through proactive diplomacy.

For clarity, this article borrows from my previous work on middle-power cooperation in the maritime domain of the Indo-Pacific to define neo middle-power diplomacy in the following manner:

[N]eo- middle power diplomacy is understood as proactive foreign policy by middle powers that actively aims to shape regional order through aligning collective capabilities and capacities.

What distinguishes neo-middle power diplomacy from so-called traditional middle power diplomacy is that neo-middle power diplomacy moves beyond the focus of buttressing existing international institutions and focusing on normative or issue-based advocacy such as human security, human rights or the abolition of land mines, to contributing to regional/ global public goods through cooperation, and at times in opposition to, the middle powers’ traditional partner, the US.

Areas of cooperation [may include] … maritime security, surveillance, HADR, joint transits, amongst others.

This article will be organized into four sections. Section one briefly examines the current Quad members, their characteristics, defense budgets, identities, and the deployment of their military and defense assets. This section serves to highlight the diversity of states that form the Quad as a basis for thinking about which states would be suitable candidates for future inclusion if the Quad evolves toward a Quad Plus.

The second section then examines the converging and diverging interests of the current members of the Quad to pinpoint where and how additional members, in this case Canada, could contribute to the Quad.

The third section then looks at Southeast Asia’s views of the Quad as a criterion to understand how the region that forms the central locus of the Quad’s activities views the Quad and what trajectory they would like to see the Quad evolve toward.

The fourth section will then discuss Canada’s role in a Quad Plus arrangement based on the analysis in the previous three sections.

The Quad’s Nuts and Bolts

By examining the current make-up of the Quad, we can make several observations that contribute to answering the research questions laid out at the onset of this article.

First, the Quad currently consists of the United States and three middle powers: Australia, India, and Japan.

Among them, Australia is a self-professed middle power that belongs to middle-power groups such as MIKTA, an informal foreign ministry-led partnership between Mexico, Indonesia, South Korea, Turkey, and Australia.

India is considered a future great power, while Japan, arguably a great power in terms of potential, behaves as a middle power by maintaining of the international order through coalition-building, by serving as mediators and go-betweens, and through international conflict management and resolution activities.

As outlined in the Lowy Institute’s Asian Power Indices between 2018 and 2020, the fluidity of the power, capacities, and capabilities that each of the current Quad members possesses, suggests that any institution based on contemporary metrics of each state’s capacities, may be outdated as the balance of power in the region continues to shift toward China.

The fluidity of power and the shift toward China are even more salient in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, as China has enhanced its assertive behavior in its periphery, evidenced by the Sino–Indian border violence in May, hyperbole toward Taiwan, enhanced gray-zone and bluehull naval operations in the South China Sea and East China Sea, and the adoption of the new National Security Law in Hong Kong in June 2020.

Second, in terms of defense spending, the current Quad members bring significant resources to the Indo-Pacific table.

In order of defense budgets, the United States brings approximately 750 billion USD, India 61 billion USD, Japan around 49 billion USD, and Australia 26 billion USD to the collective military resources of the Quad.

Despite the pandemic-induced global recession, each of the current Quad members continues to increase their defense budgets to reflect the realization that more and more resources will need to be directed at the Indo-Pacific, to ensure the region is not shaped by China unilaterally.

For instance, the July 2020 Australian Strategic Defence Update envisions a region that will demand more robust maritime, submarine, and strike capabilities to defend itself in the coming decades.

In its 2021 defense budget request, Japan plans a record 5.49 trillion Yen, focusing on space, cyber, and the electromagnetic spectrum. These are meant to deal with immediate challenges, such as North Korea’s weapons of mass destruction and missile development, and the long-term challenge of China’s reemergence as the dominant organizing state in the region, and determination to reorganize the region to protect Beijing’s core interests.

The United States and India have increased their military budgets as well. In the case of the United States, its Indo-Pacific Strategy and defense budget proposal demand increased resources be developed and deployed in the region to counter China’s revisionist behavior.

India continues to increase its military spending to push back against a growing Chinese maritime presence in the Indian Ocean, a military presence along the Indo–China border, and China’s support for India’s archrival, Pakistan.

Third, if we compared where most of the defense and military assets are deployed, we find that Japan, Australia, and India have deployed most of their assets in their near abroad.

For Japan, that means throughout the Japanese archipelago, the East China Sea, the South China Sea, and parts of the Indian Ocean.

Australia, in contrast, has deployed the majority of its military assets in the Pacific Islands area, South China Sea, and parts of the Indian Ocean.

India deploys most of its assets in the Indian Ocean and along its northern borders with China and Pakistan.

Even though the United States has a global deployment of its assets, it started titling its resources to the Asian region, first under the Obama administration’s Rebalancing Strategy, and accelerated under the Trump administration through its Indo-Pacific Strategy.

Converging and Diverging Interests of Quad Members

Another important area to examine when thinking about the Quad and attempting to carve out a role for middle powers is to examine the converging and diverging interests of its current members to identify synergies and opportunities to establish a Canadian middle-power role.

For existing Quad members, there are many areas of convergence.

The most imminent concerns for them are growing economic interdependence with China and China’s track record of using economic coercion as leverage for strategic gains.

China’s surrogates in Northeast Asia and South Asia, in particular nuclear weapons development in North Korea and Pakistan, also create worries in Japan and India.

China’s objection to expanded representation in the United Nations Security Council, despite attempts by Japan and India, represents another shared concern for Quad members.

China’s expanding maritime claims in ESC, SCS, and Indian Ocean have the potential to disrupt sea lines of communication (SLOC).

Furthermore, Quad members are united in their continued frustration with China’s role in fracturing Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) unity.

Finally, there is also growing interest among Quad members to use arrangements such as the Quad to enhance partnerships through specific initiatives such as strengthening and diversifying global supply chains.

India sees the Quad as a coalition of states to sustain the US presence in the region. The subtext here is to ensure the Indo-Pacific region and the Indian Ocean are not dominated by China as Beijing seeks to elevate its global reach through the construction of ports and infrastructure through the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and other arrangements in India’s neighboring states of Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, and Pakistan.

For India, Chinese infrastructure projects are strategically located in what India deems its historical sphere of influence and are often called China’s string of pearl around India’s neck—albeit viewed more as a garrote than a necklace.

New Delhi’s views of the Quad partially overlap with those of Tokyo and Canberra in this regard, as all three states want to ensure that the United States remains engaged in the region through active institutional arrangements such as the Quad.

While convergences are many, there are important divergences that continue to make deeper institutionalization of the Quad a challenge.

For India and Japan, issue linkage over North Korea and Pakistan’s nuclear capabilities continues to foster disagreement.

Tokyo would like to get India’s support for North Korea, and New Delhi seeks Tokyo’s support for Pakistan, but neither side is willing to seriously support the other’s concerns.

Another area of divergences is Tokyo, Washington, and Canberra’s comfort with alliances, alignment, and minilaterals, whereas New Delhi continues to wed itself to the Non-aligned Movement.

More critically perhaps is the gap between New Delhi and its Quad counterparts in terms of the geographic understanding of the Quad and the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP).

Here, India sees the Indian Ocean as the geographic scope of the Quad’s activities, whereas the other members of the Quad have much more expansive understandings.

Last but not least, each member of the Quad has different degrees of concern regarding the securitization of the Quad or FOIP.

For India, Japan, and Australia, their largest trading partner is China, and that relationship cannot be easily changed.

Table 1.0 Japan–Australia–India–US and Canada’s converging and diverging interests

| Japan–Australia–India–US and Canada | Concern | |

| Converging Interests | 1. Growing economic interdependence with China (Glaser, 2017) 2. Chinese surrogates in Northeast Asia and South Asia 3. UNSC permanent member status (Mohan, 2013, 283) 4. China’s expanding maritime claims in ESC, SCS, and Indian Ocean (Abe, 2015) 5. China’s role in fracturing ASEAN unity 6. Resilience of Global Supply China (Basu, 2020) 7. Infrastructure, connectivity | 1. Economic coercion 2. DPRK, Pakistan (missile and nuclear tech) 3. Monopolization of representation 4. Sea lines of communication 5. ASEAN Centrality 6. Global supply chain disruption 7. Development, integration |

| Diverging Interests | 1. Issue linkage (Panda, 2011, p.8) 2. Alliance/alignment/minilaterals 3. Competing visions (Roy-Chaudhury and Sullivan de Estrada, 2018) 4. Over- securitization of Quad or FOIP | 1. North Korea vs Pakistan 2. Legacy of Non- aligned Movement, US–Japan Alliance, Transpolar Sea Route 3. Indian Ocean vs Indo- Pacific 4. Exclusion of China and conflict |

The Quad and Southeast Asia

From the vantage point of Southeast Asia, the Quad in its current form is unlikely to get regional buy-in from ASEAN or Southeast Asian states. First, there is no dominant view within the region as to how to engage the Quad.

Even Vietnam and the Philippines, the two countries with strong anti- Chinese sentiment, would not like to see the Quad evolve into a hard security- focused regional institution, as it would place them in a position in which they need to choose between their security and their economic prosperity.

Both would welcome the Quad as a new actor in the region, depending on what the Quad intends to do. For them, the right formulation of the Quad would be another tool to hedge against China.

Other Southeast Asian states do not view the Quad in such utilitarian manner. For many, if the US–China rivalry is the basis for the Quad, it becomes an initiative that ASEAN will be unable to support.

That said, for most, the Quad is another tool in the hedging box and a useful means to keep the United States engaged and to bring in other stakeholders to maximize the strategic autonomy that ASEAN carefully guards.

If the evolution of the Quad focuses on maritime security, there is more potential to get support from ASEAN.

In the COVID-19 pandemic era, other areas have emerged as potential pillars

of cooperation that could be implemented by the Quad countries in their present form or an enlarged Quad Plus format.

For instance, COVID-19 demonstrated the vulnerabilities that Southeast Asian states face in terms of supply chains and in particular the vulnerability of their medical supply chains.

States like Vietnam and Cambodia, which are deeply dependent on China’s supply chains, are increasingly in need of finding ways to diversify their trade and supply-chain portfolio to preserve their strategic autonomy as the US-China strategic competition intensifies.

The Quad represents one of many tools the region can use to meet its needs. To capitalize on this, the Quad needs to be reinvented to focus on the needs of Southeast Asian countries rather than some kind of Indo-Pacific NATO arrangement to contain China.

Here, Japan’s FOIP and its overlap with aspects of the Quad in terms of membership and several policy agendas may be a template to get support from Southeast Asian countries for not only a more proactive role for the Quad in the Indo-Pacific but importantly, expanded membership to bring in more resources to the region.

Critical to garnering support will be the inclusion of a clear statement supporting ASEAN Centrality, an overt shift toward infrastructure and connectivity, development, and trade as the key pillars of a reinvented Quad.

An example the Quad can follow is FOIP’s shift away from a more security- focused FOIP 1.0 to what Hosoya Yuichi of Keio University calls FOIP 2.0, a revamped FOIP that is more in line with the needs of the littoral states in the Indo-Pacific.

Quad Plus?: Carving Out Canada’s Middle-Power Role

Shifting to the central research puzzle of this article regarding a possible role for middle powers such as Canada in a Quad Plus arrangement, it is useful to first provide a brief overview as to Canada’s engagement in the region, followed by a systematic examination of where Canada fits compared to existing Quad members and in an expanded organization.

Canada’s hitherto engagement in the region has been through an Asia-Pacific, not an Indo-Pacific framework, focusing on multilateral architecture such as the Asia- Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) on the trade side.

Canada was a founding member of APEC in 1990 and has been a dialogue partner in the ARF since the forum’s formation in 1994.

Canada’s activities in the region also include international development in the form of support, cooperation, and membership in the Asian Development Bank (ADB), and more recently joined – while not before considerable internal debate—the Chinese-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in 2017.

On the political-security side, Canada’s engagement has been through the ARF. Traditionally, this is primarily meant to strengthen cooperation among member states within the Asia-Pacific context, and now this is falling increasingly under the umbrella of the Indo- Pacific framing.

Canada has yet to find a way to contribute to the region’s security architecture

through institutional participation. Nevertheless, Canada actively participates in multilateral defense fora such as the Shangri-la Dialogue, the Tokyo Defense Forum, the United States Pacific Command Chiefs of Defense Conference, the Jakarta International Defense Dialogue, the Multinational Planning and Augmentation Team Program, and the Seoul Defense Dialogue, which bring together senior defense officials at the deputy minister/vice minister level. Canada continues to express its interest in becoming a member of both the ASEAN Defence Ministers’ Meeting–Plus and the EAS.

Currently, Canada’s regular military activities in the Indo- Pacific area include the biennial Rim of the Pacific Exercises (RIMPAC). In 2014, Canada deployed more than 1,000 Canadian Armed Forces personnel; ships, such as the HMCS Calgary, HMCS Nanaimo and HMCS Whitehorse; submarines, such as the HMCS Victoria; and several aircraft (eight CF-188 Hornets, one CC-130 Hercules, one CC-150 Polaris, and three CP-140 Auroras).

In addition to these multilateral exercises, Canada also participants in the Cobra Gold, one of the largest exercises in the region next to RIMPAC; ARF’s disaster relief exercise (DiREx), which is a training opportunity through which ASEAN countries can exercise coordination of civil- military international assistance to strengthen cooperation in HA/DR cooperation; and Ulchi- Freedom Guardian Exercise, which tests the operational control of the combined forces in defense of the Korean Peninsula. Canada’s participation has consisted of personnel from the 1st Canadian Division, acting as a Division Headquarters under the the 1st US Corps, among other military training exercises in the region.

Reflecting on Canada’s participation in multinational defense fora and its interests in the Quad, there is a convergence on many issues in the Indo- Pacific region – but less so as to the nature of the Quad.

In fact, little is written about Canada’s perception of the Quad, with some mischaracterizations such as “the Quad is nowadays contextualized first of all by issues around the militarization of Chinese international behaviour,” an impression of the Quad which resonates with Southeast Asian states and other states as well.

Comparing to the other middle powers within the Quad, Canada spends around 22.5 billion USD per year, a number that is comparable to Australia but well below the other Quad members’ budgets.

Ottawa deploys most of its resources toward NATO-related activities and peacekeeping operations. It was only in 2012 when Canada began its “mini-pivot” to the Asia- Pacific in which we saw regularized Canadian ships visits to the region.

These activities have continued to expand, with the Canadian navy seeing greater engagement in Asia. Still, a common refrain when advocating for enhanced security-related engagement in the Indo-Pacific is that Canada already is significantly overstretched to manage its security in the Pacific, Atlantic, and now the Arctic Oceans and that it is simply impossible to divert more resources to the Indo-Pacific in any meaningful manner outside the regularized joint exercises listed above.

If that is the case, Canada’s ability to contribute to the Quad’s capacities significantly is limited by the realities of finite resources. Nonetheless, that does not mean that Canada cannot contribute to the Quad in other areas, such as enhancing maritime domain awareness activities, HA/DR operations, international development, infrastructure, and connectivity.

As Robert M. Cutler writes, Canada can even assume the role of a stable “producer and exporter of Canadian oil and gas to Canadian allies in the Indo- Pacific region.” In this sense, Canada’s potential role within the Quad will depend less on who is part of the Quad or Quad Plus formulation but rather on what activities the Quad members agree to be the core agenda of the nascent institution.

If the Quad evolves toward a security grouping aimed at curbing China’s assertive behavior in the Indo-Pacific, the contributions that Ottawa could practically provide would be limited to enhancing the capacities of the other members through leveraging Canada’s experience and expertise in particular maritime- based activities such as maritime domain awareness.

In discussions with Canadian naval personnel, the core competences that Canada could provide in maritime domain awareness is leveraging their intelligence-gathering experience and expertise to bolster the collective capabilities of Quad members.

This targeted form of collaboration suggests that there might be scope for other forms of targeted cooperation within the Quad framework as well. These may include multilateral sanctions enforcement in the case of North Korea, capacity building, search-and-rescue operations, and HA/DR activities.

If the Quad evolves in a direction that inculcates the needs of Southeast Asian states such as development, the diversification of global supply chains, infrastructure and connectivity, and nontraditional security cooperation such as antipiracy, antipoaching, illegal immigration, and food security, Canada will have more latitude in terms of the meaningful contributions it could provide to a revamped Quad.

Here, Canada’s existing track record in international development could be leveraged alongside Quad members such as Japan, which already has an established, longstanding track record of providing official development assistance (ODA) for regional development. This could be through the ADB, the AIIB, or both, depending on the project and target of developmental aid.

In the area of non-traditional security cooperation as well, there is extensive overlap between the maritime domain awareness operations to monitor blue- and white-hull ships of sanction evaders and states attempting to dominate the ECS and SCS and the monitoring of pirates, illegal fishing, and human trafficking.

Contributing to capacity building of states on the frontline of Chinese assertive behavior will be critical. This means providing training and tools such as coast guard vessels, maritime domain awareness technologies, and intelligence so that states in the region can manage their bilateral challenges with China on more even ground. It also means more joint training exercises focusing on HA/DR and search-and-rescue to develop interoperability and experience.

Building on Canada’s preexisting bilateral relations with each of the current Quad members, established multilateral cooperation in institutions such as the

Five Eyes, and joint training exercises with Australia, Japan, and the United States, Canada is well positioned to contribute directly to current Quad members directly within or outside the Quad framework.

Canada has activity courted India to expand cooperation in many areas, including the Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreement (FIPPA) and the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) under former Prime Minister Stephen Harper.

Harper further expanded cooperation to include foreign direct investment, technology transfers, and trade agreements and leveraged diaspora links toward expanding ties with India.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau further deepened this engagement with India with the recognition of “the rapid emergence of the global South and Asia and

the need to integrate these countries into the world’s economic and political system.”

Ottawa’s courting of New Delhi was aimed at inculcating stability into the Asia-Pacific with the rise of China and its assertive behavior in the region.

While not explicitly supporting freedom of navigation operations (FONOPS) in the Indo-Pacific and not linking Canada’s activities in the Indo-Pacific to Chinese maritime behavior, Ottawa has aimed to both support and enhance Canada’s relationships with states like India in the region at the same time it engages with China.

Infrastructure, connectivity, and energy remain areas of synergy between Canada and India. Working through the Blue Dot Network, Ottawa could leverage Canada’s preexisting capacities and cooperate with Australia, Japan, and the United States to undertake infrastructure and connectivity projects to help New Delhi develop India’s smart cities, diversify global supply chains, and make India and the region more resilient to shocks to supply chains and economic coercion.

Energy is another area that Canada could lend weight to relieve pressure on states with concerns over SLOCs in the SCS being disrupted by intentional or

accidental conflicts in the region.

By providing a steady flow of energy resources to the region, Canada could assist Quad members and Southeast Asian states to be less dependent on energy flows in the SCS.

For Southeast Asian states, this gives them more strategic autonomy by decreasing their reliance on SCS-based SLOCs.

For Quad members, guarantees of stable supplies of energy strengthens their resilience against disruptions, allowing their economies to be less affected by conflict, coercion, and endogenous and exogenous shocks.

On the energy front, Canada is already reaching out to India. For instance, at the second India–Canada Ministerial Energy Dialogue, Minister of State for Petroleum and Natural Gas Dharmendra Pradhan said, “India and Canada share common values and ideals and believe in long term sustained partnerships. Our energy cooperation is steadily growing, but the potential is much higher.”

Ketan Metha highlights that: “In times of growing pressure from the US to cut oil imports from Iran, Canada could be an alternative energy source for India. Canada can also be a significant source of Liquified Natural Gas (LNG) for India. It is estimated that the latter will import 44 billion cubic metres of LNG by 2025.

Aside from India, Canada has also reached out to the other existing Quad members to provide support for cooperation and a growing alignment of the FOIP vision.

For instance, on the occasion of Canadian defense minister, Harjit Sajjan’s visit to Japan, in June 2019, both countries agreed to continue to advance the FOIP.

This declaration came in the wake of the previous years’ Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement, to strengthen cooperation between the Canadian Armed Forces and the Japanese Self-Defense Forces.

The agreement advances cooperation between the two countries in response to humanitarian and disaster crises, peacekeeping initiatives, and allow greater collaboration with third-partners, including the US.

Cooperation between Canada and Japan is not limited to the bilateral level as highlighted above. Since 2018, Canada has also participated in the Keen Sword trilateral exercises with the United States and Japan.

The latest rendition of Keen Sword included one Canadian Destroyer, and is meant to provide participants a comprehensive scenario designed to exercise the critical capabilities required to support the defense of Japan and respond to a crisis or contingency in the Indo-Pacific region.

While participation is modest, the regular presence of the Royal Canadian Navy working alongside Japan and the United States sends a strong signal, that Canada is committed to working with like-minded countries in the Indo-Pacific on issues Ottawa deems critical to a rules-based order.

This participation outside the Quad framework and without signing on to the Freedom of Navigation operations, the latter of which is squarely aimed at deterring Chinese maritime activities, does not speak to Canada’s lack of support for these activities; rather, it illustrates that Ottawa wishes to maximize Canada’s strategic flexibility toward China, while demonstrating Canadian support for and ability to contribute to multilateral cooperation in the region.

Maritime monitoring and surveillance is another domain in which Canada has been engaged since 2018, using aircraft based at Kadena Air Base, Japan, and subject to a UN Status of Forces Agreement, to counter illicit maritime activities, including the ship-to-ship transfers of North Korean-flagged vessels that are prohibited by United Nations Security Council resolutions.

Here, leveraging the preexisting Five Eyes Network provides a springboard to expand cooperation between current Quad members, such as Australia and the United States, while at the same time basing cooperation on the Five Eyes framework excludes two of the current Quad members: Japan and India.

Canada recently held a virtual Five Eyes defense ministers’ meeting on 15–16 October 2020. Building on the June 2020 Five Eyes meeting, participants expanded their talks to focus on China and the Indo-Pacific. This focus may provide a framework where Canada can provide value in the Indo-Pacific.

While this maybe be welcome to identify where current and potential Quad members could cooperate, some see a Five Eye framework for Canada to participate in the region a “risk that by diluting an intelligence-sharing and joint collection mechanism into something with an expansive agenda, the core missions of the grouping could be sidelined. Issues-based coalitions work much better than all-purpose ones.

Last but not least, the COVID-19 pandemic and a recent track record of economic coercion clearly illustrated the dangers of global supply chains being overcentralized in one state.

In the case of the former, the shutdown of the Chinese economy to control the COVID-19 outbreak severely affected the supply and distribution of products, including medical equipment and personal protective equipment, parts, and products to the world.

In the case of the latter, economic coercion against Australia, Canada, South Korea, and Japan in recent years demonstrates the need to diversify and strengthen supply chains such that countries can be better positioned to deal with shocks to global supply chains and the weaponization of trade.

To do this, Japan’s approach has been primarily economic. It is investing in building resilience into the Indo-Pacific economic integration through infrastructure projects, strengthening global supply chains throughout Southeast and South Asia, developmental and technological aid that strengthens economic integration, support for a shared rules-based understanding of trade, and the use of sea lines of communication.

To illustrate, the supplementary budget for fiscal 2020 includes subsidies to promote domestic investment for support of supply chain (220 billion Yen) and for supporting di- versification of global supply chains (23.5 billion Yen).

These are examples of this investment during the COVID-19 pandemic, but many of the core pillars of the FOIP Vision also illustrate this commitment.

Taking a page from Japan’s approach to deal with economic coercion and the possibility of another shock to global supply chains, Canada should work with other Quad members in investing in the diversification and resilience of supply chains.

This serves to enhance their collective economic security while providing to Southeast Asian and South Asian states critical infrastructure and connectivity that enhances their development.

At the same time, it enhances these states’ strategic autonomy to deal with assertive behavior without directly confronting China or creating a security competition with China.

Conclusion

The viability of a Quad Plus arrangement and carving out Canada’s middle-power role is dependent on how successful current Quad members are at reinventing the security dialogue such that it focuses on the needs of Southeast and South Asian nations.

Canada’s contributions will be limited if the arrangement retains its current formulation and orientation that leans toward an informal security partnership chiefly aimed at containing China.

In contrast, a reinventing of the Quad such that it embodies the needs of littoral states in the Indo-Pacific opens up doors for Canadian contributions to the region through the Quad.

Infrastructure and connectivity, energy cooperation, maritime domain awareness, HADR, and search-and-rescue activities are the primary areas in which Canada can contribute to the current Quad and Quad Plus formulations.

For Canada, the question of a middle-power role within the Quad will be informed by how well Ottawa can leverage and expand Canada’s existing bilateral and multilateral cooperation in the Indo-Pacific to add value to the Quad while being in line with Canadian interests in the region.

Download the PDF file here:

Leave a comment